DNSSEC 1x1

Patrick Koetter und Carsten Strotmann, sys4 AG

Created: 2023-10-19 Thu 13:47

New terminology used in DNS & BIND

New DNS terms

- The terms

masterandslavehave been used to describe primary and secondary authoritative DNS servers in the past.- However this terminology is wrong and misleading, for the reasons discussed in the Internet Draft Terminology, Power, and Inclusive Language in Internet-Drafts and RFCs: https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-knodel-terminology

New DNS terms

- In this document, and in configuration examples, we are using the

new terms

primary(instead ofmaster) andsecondary(instead ofslave) whenever possible. - BIND 9 has started adopting the new terms with BIND 9.14, however

the transition is not complete and some terms in configuration

statements are still using the old terms. This will change with

future releases

- If you use an older version of BIND 9, please substitute the new terms for the older ones

New DNS terms

- The old terminology will also be found in older books and standards documents (RFCs and Internet Drafts)

- DNS terminology can be confusing and is sometimes overloaded. RFC 8499 DNS terminology ( https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc8499 ) attempts to collect and document the current usage of DNS terminology.

Recap: DNSSEC – what does it do and how does it work?

DNSSEC in a nutshell

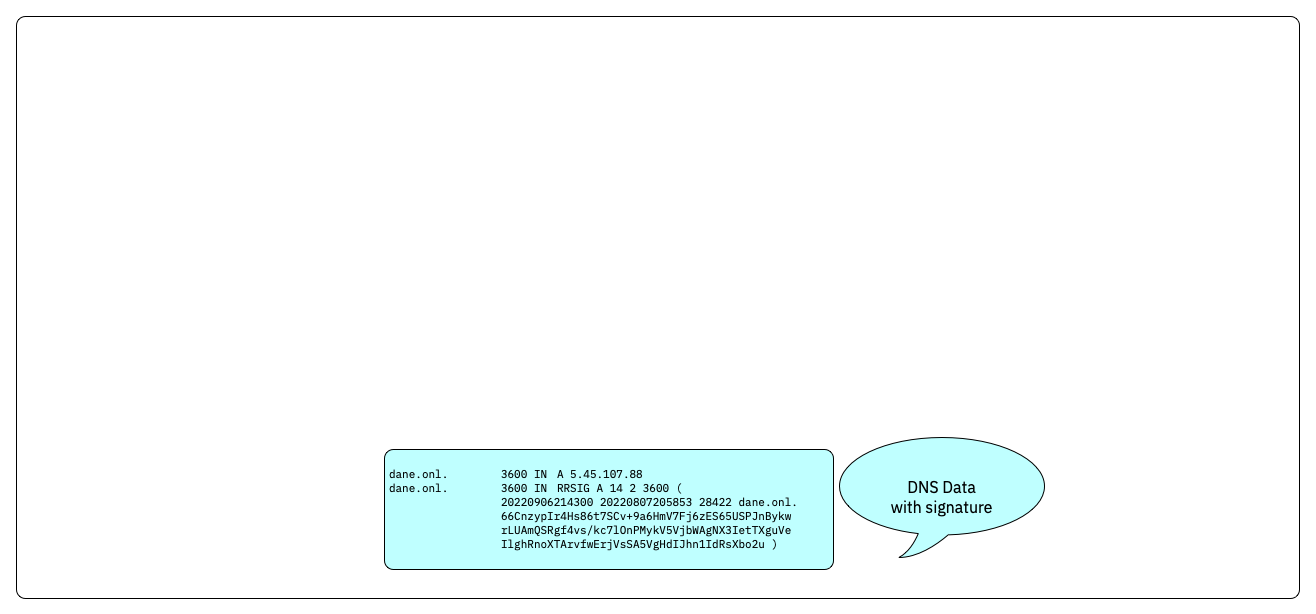

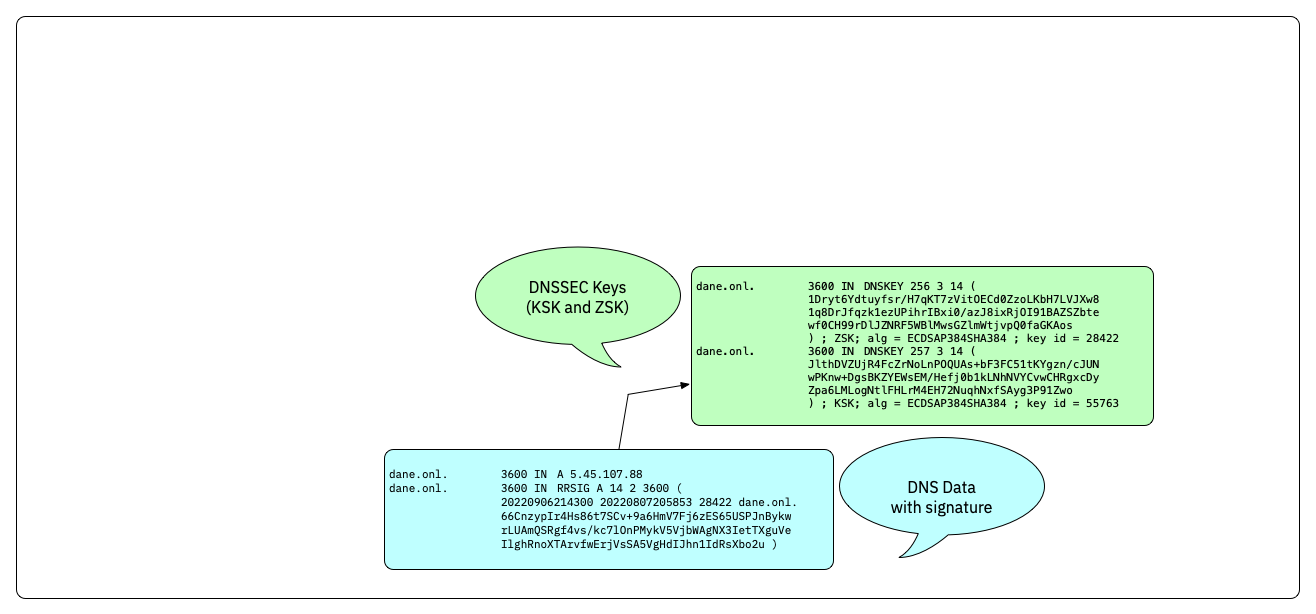

- DNSSEC augments DNS data (resource records) with cryptographic signatures

- The signatures can be validated using cryptographic keys (DNSKEY records)

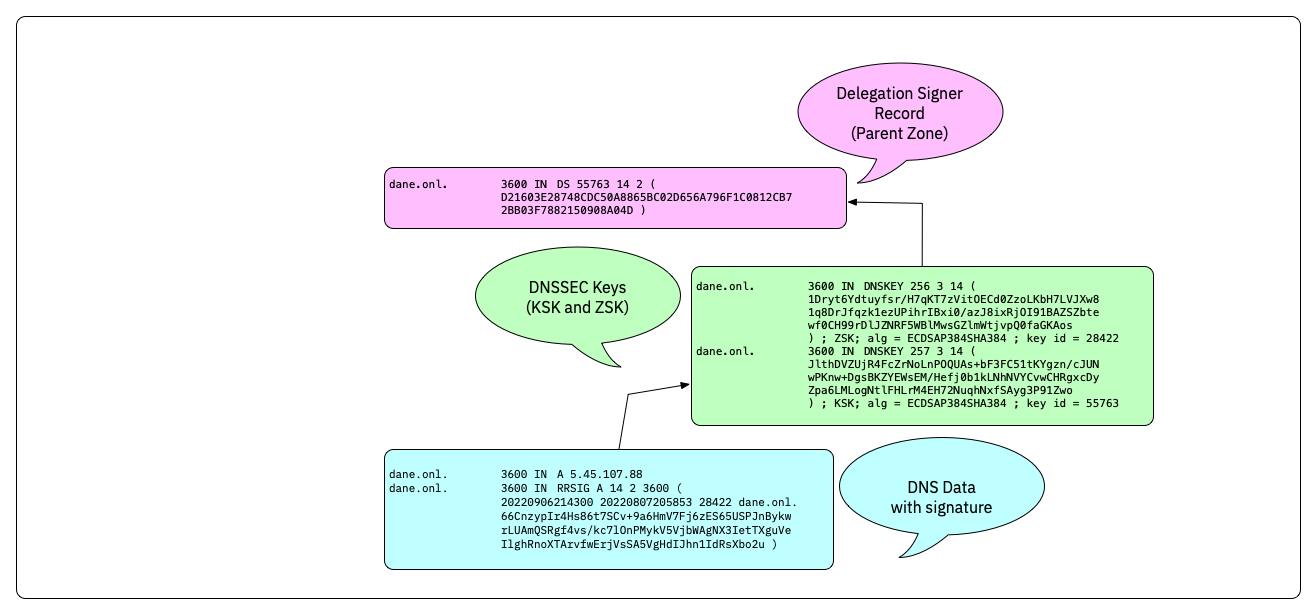

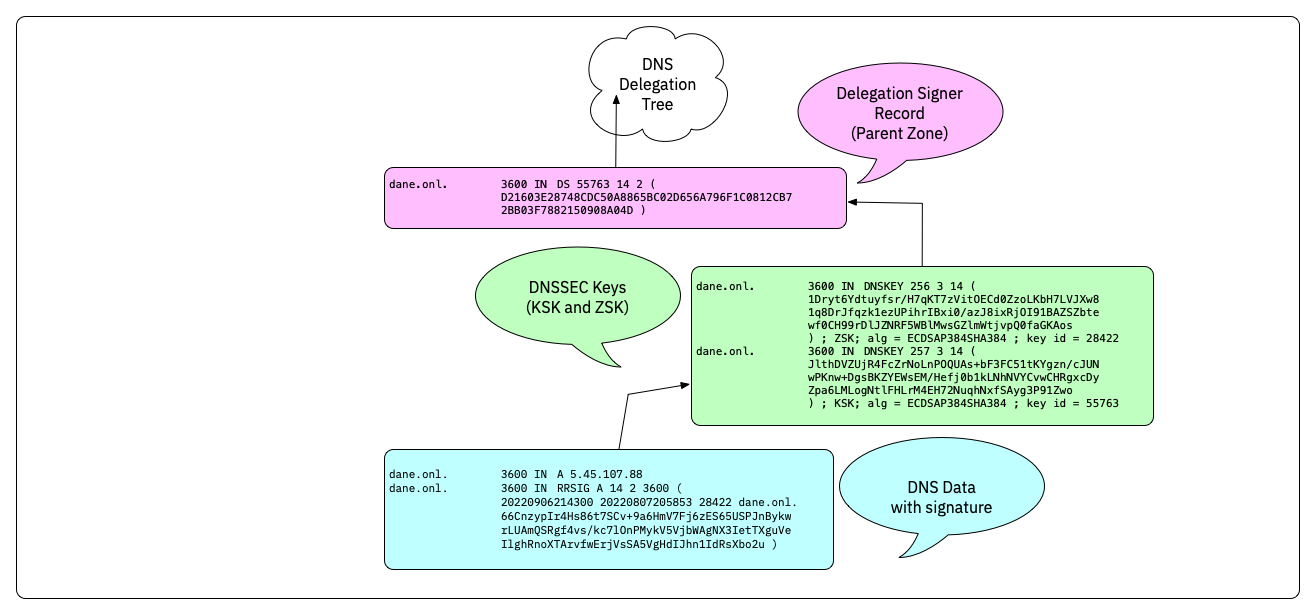

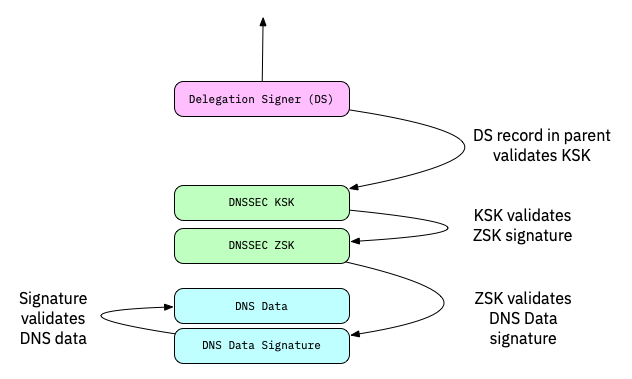

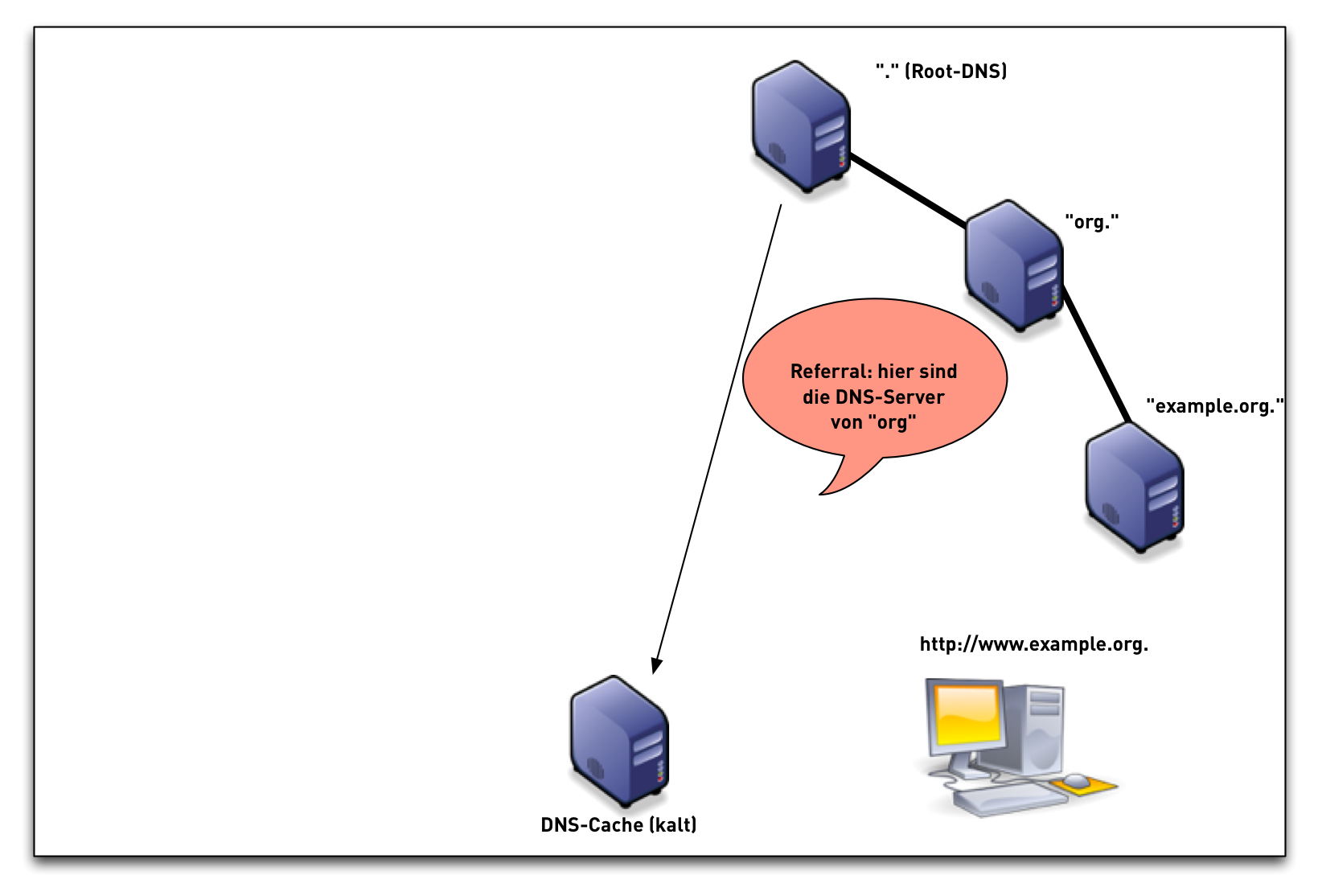

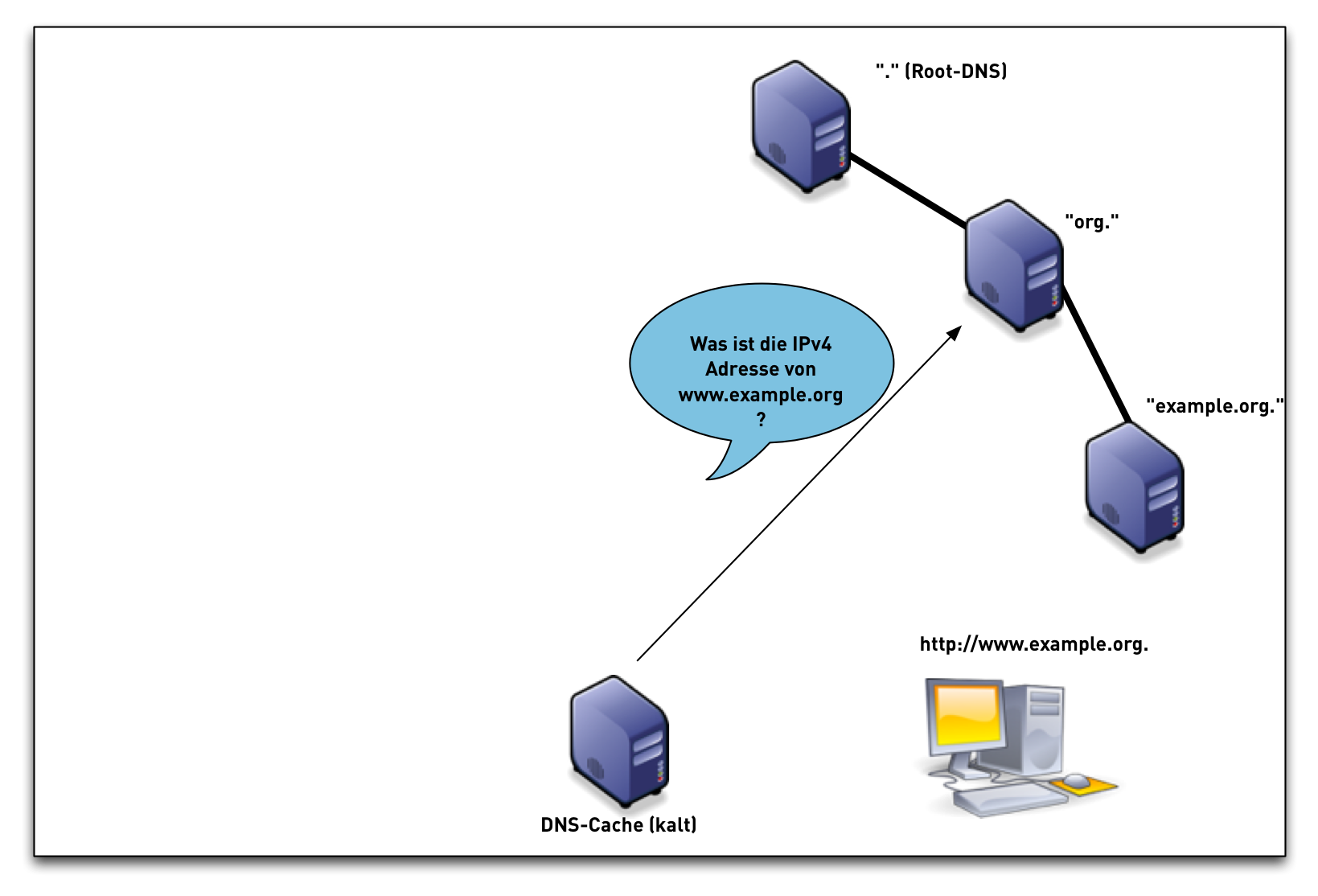

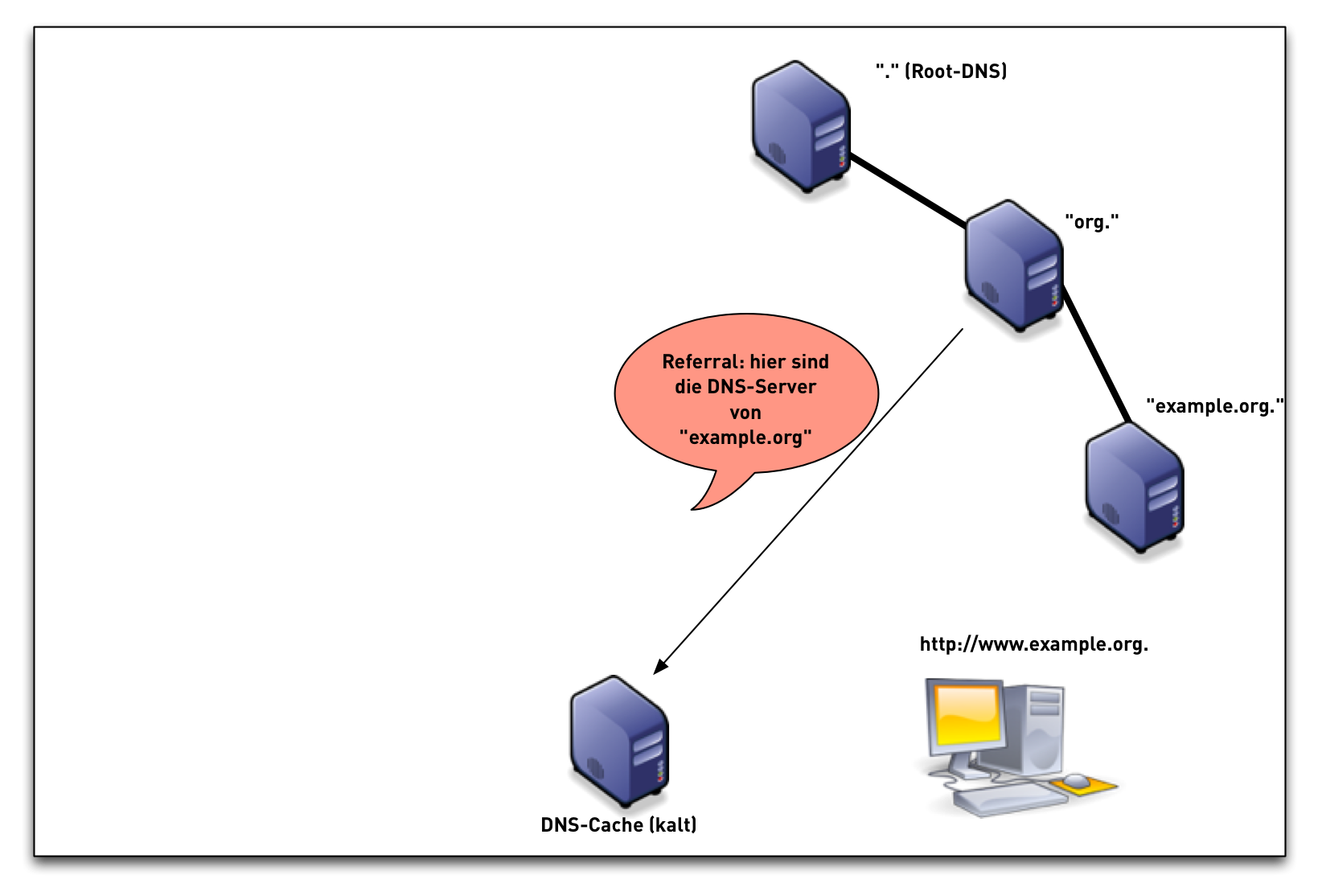

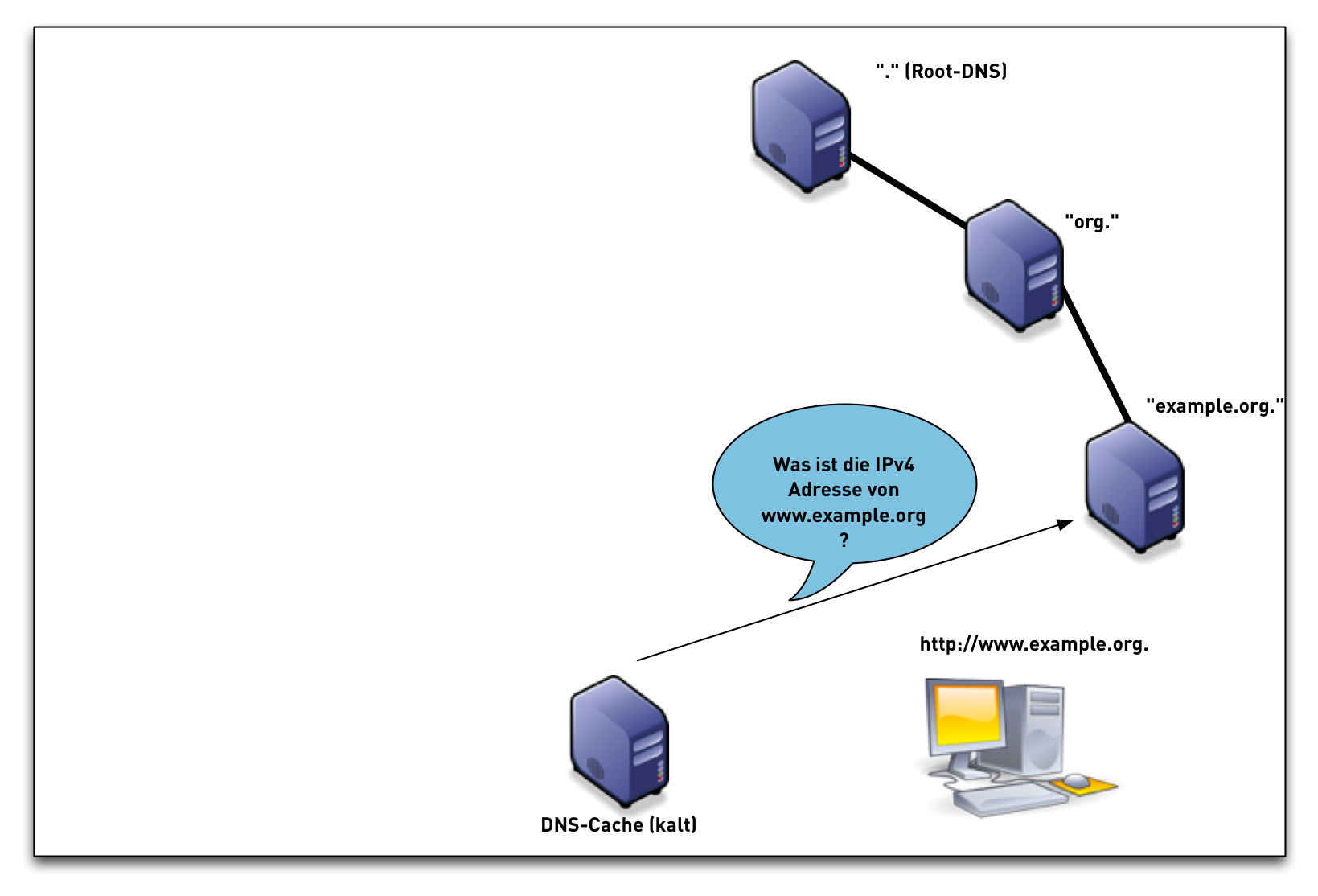

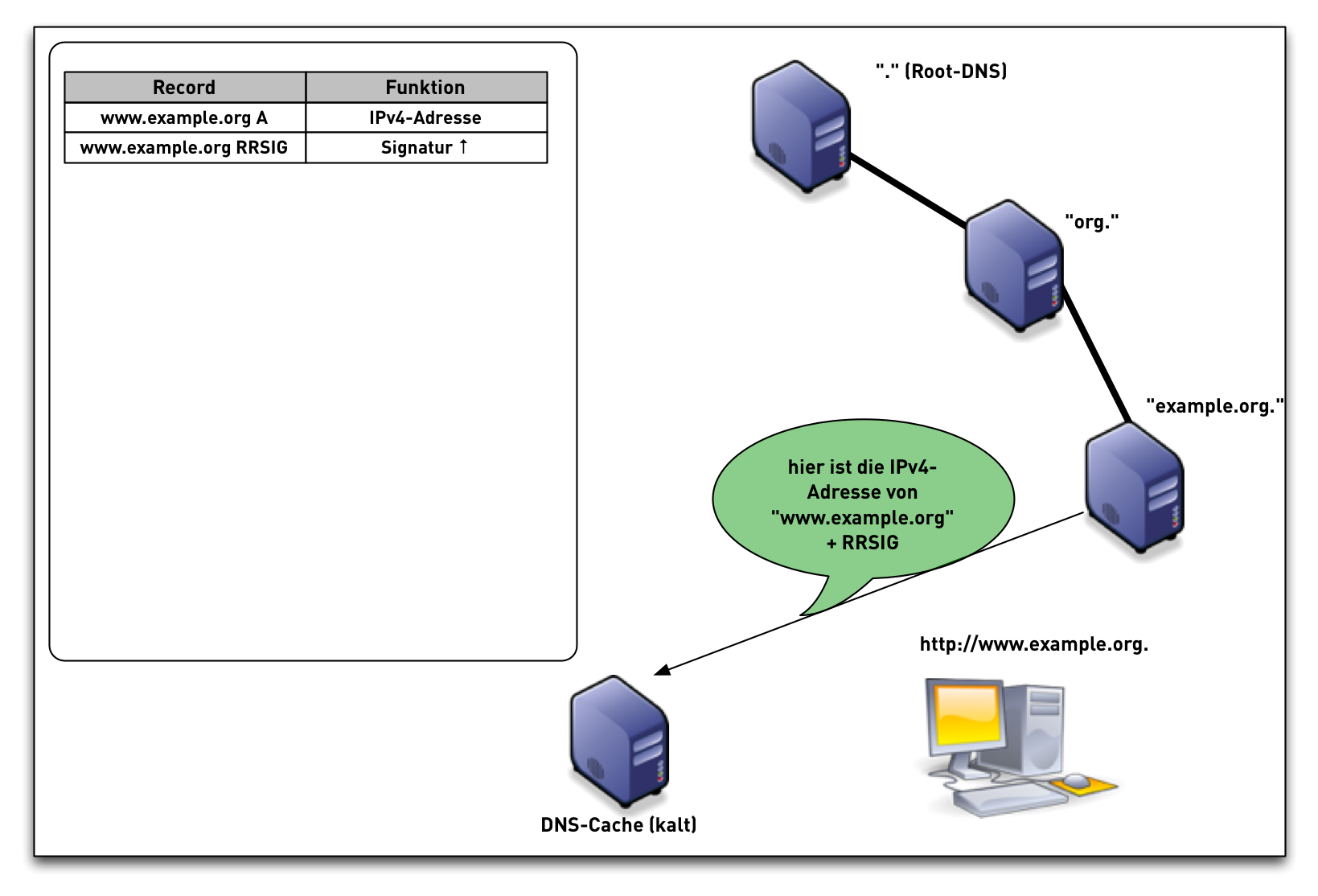

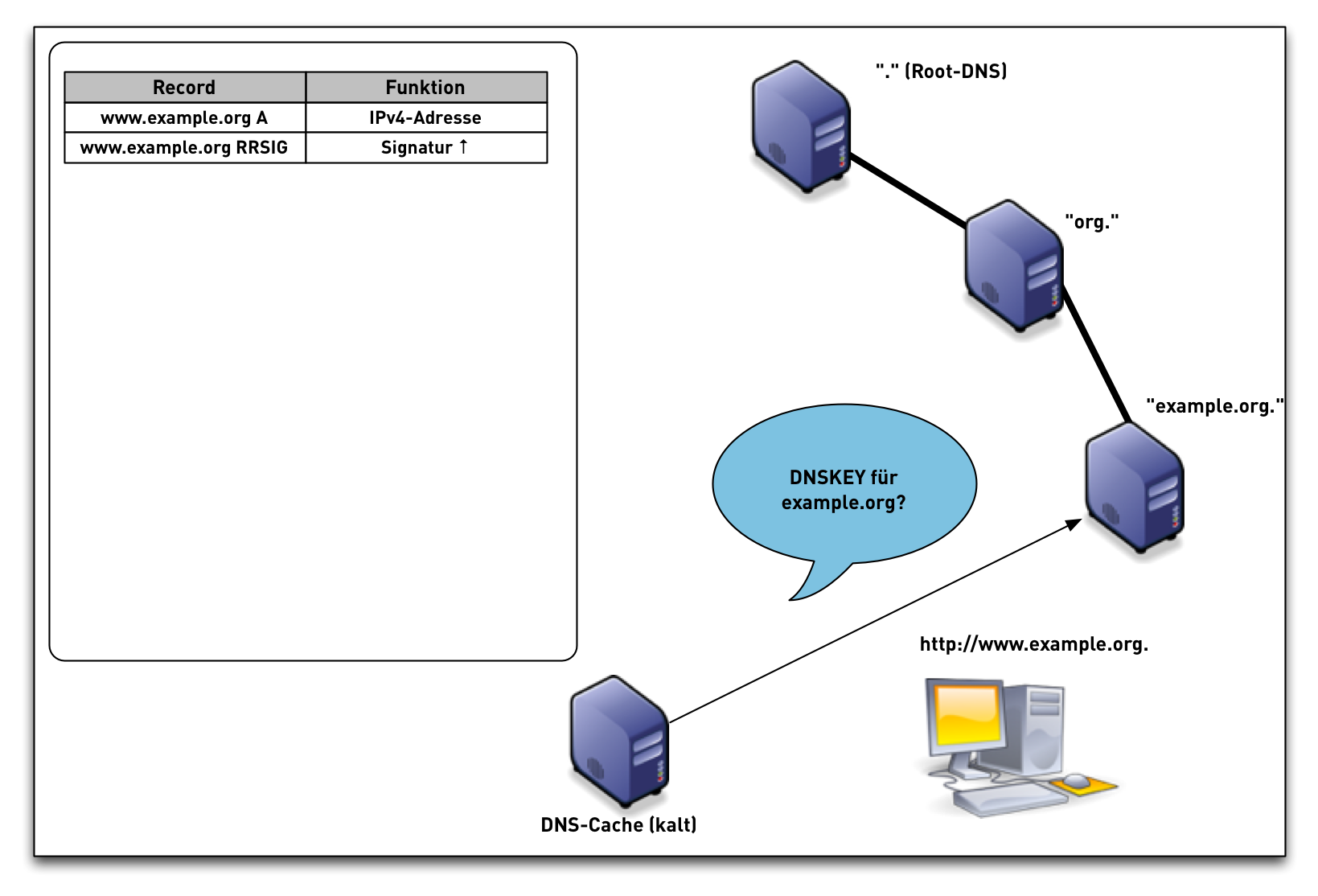

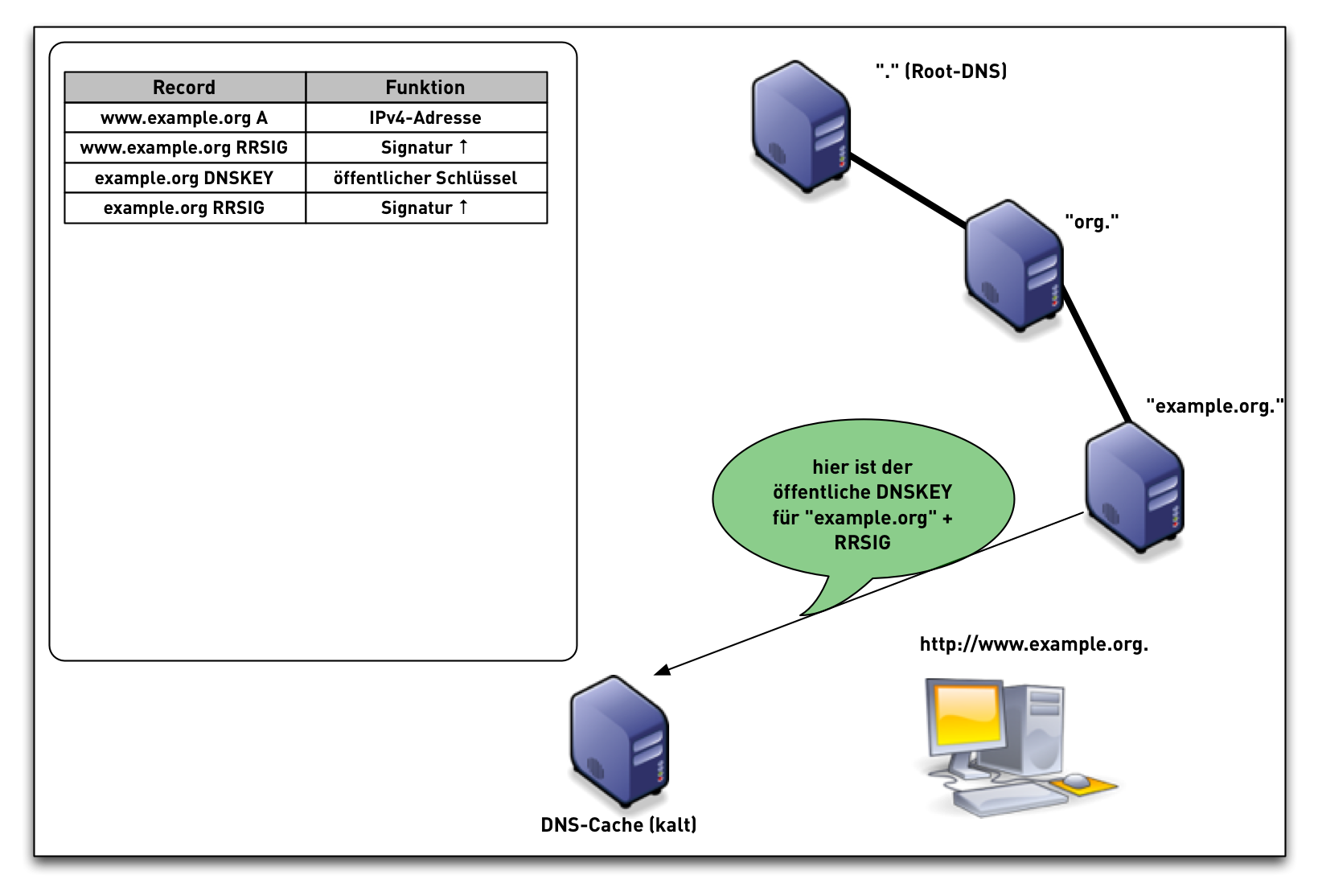

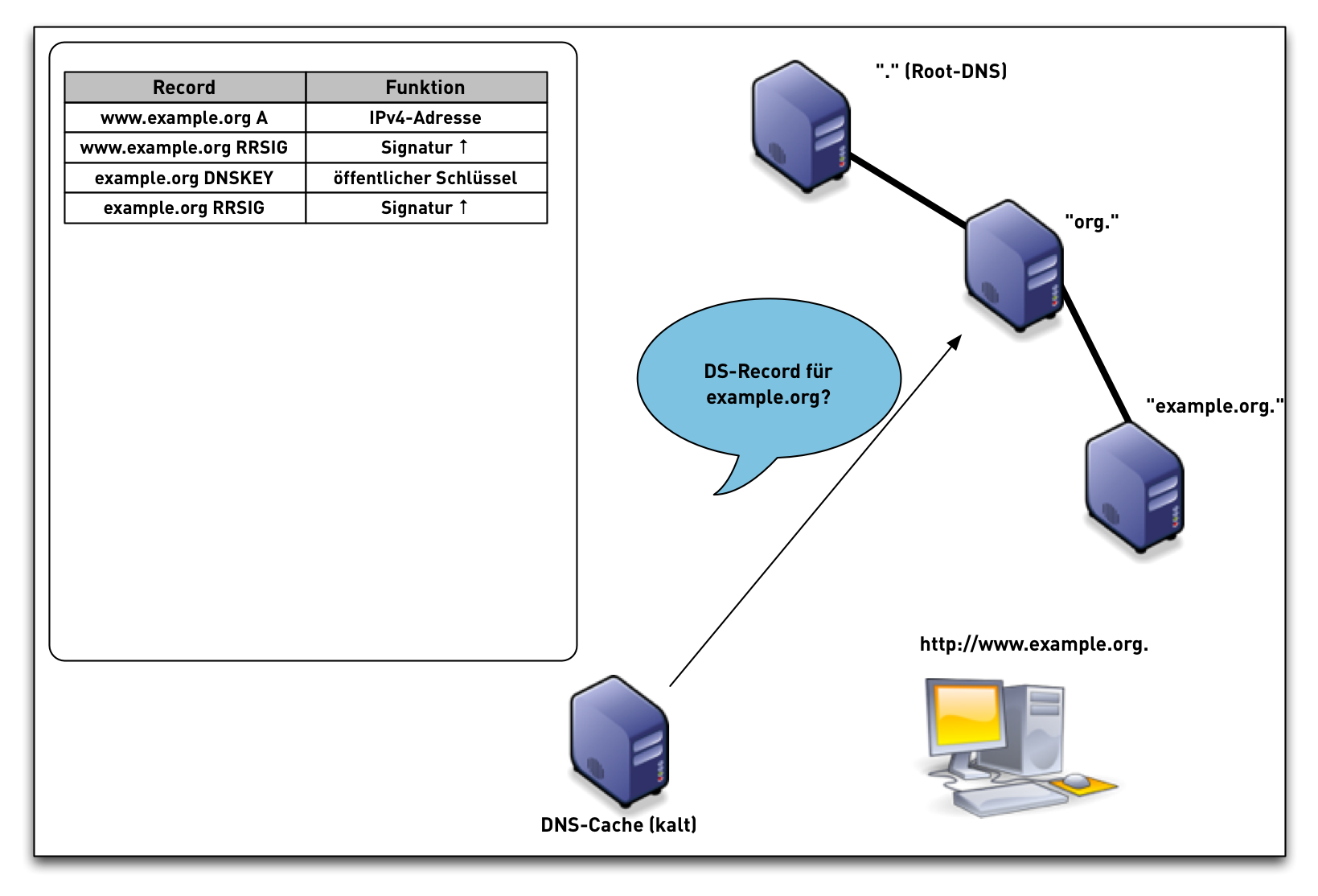

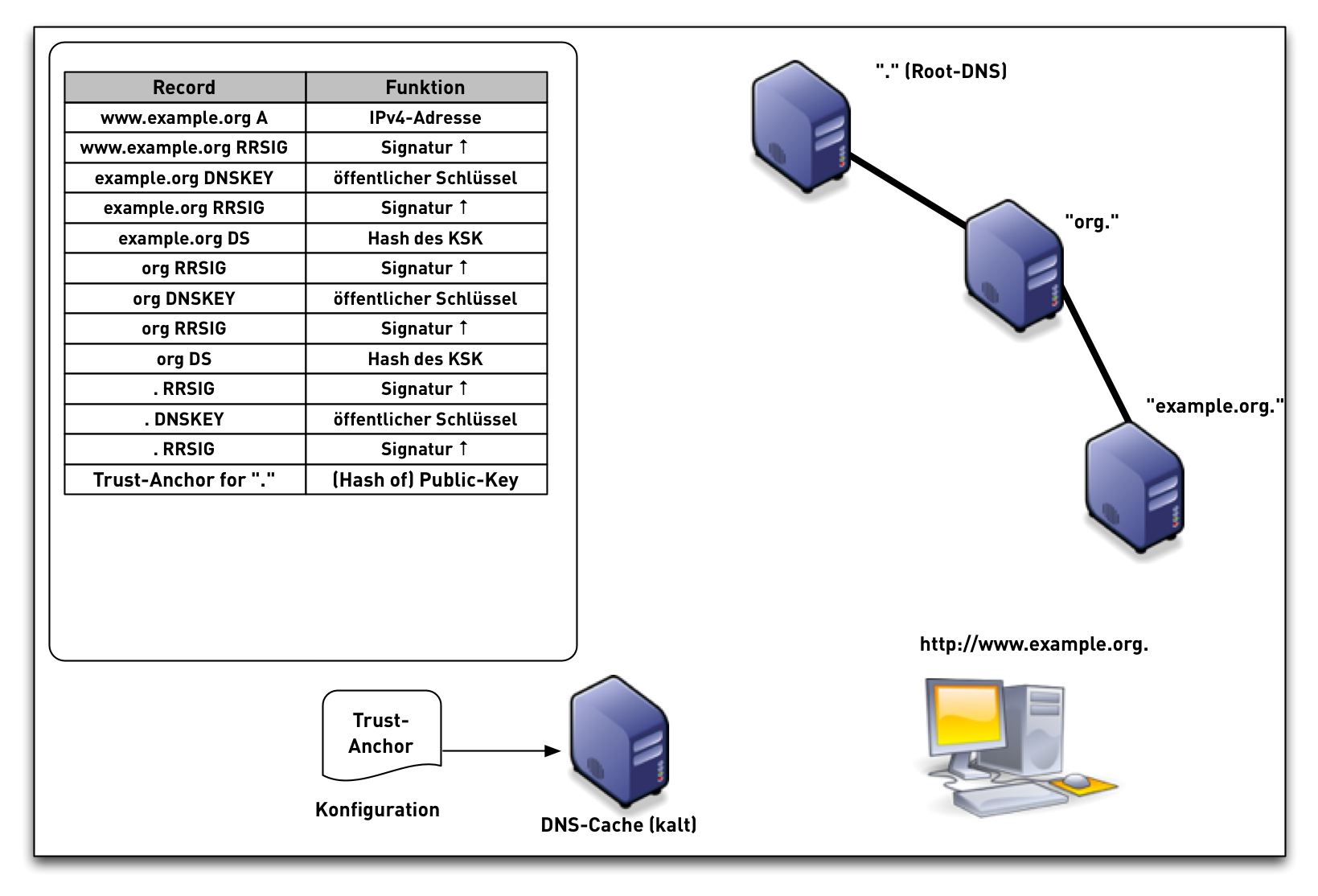

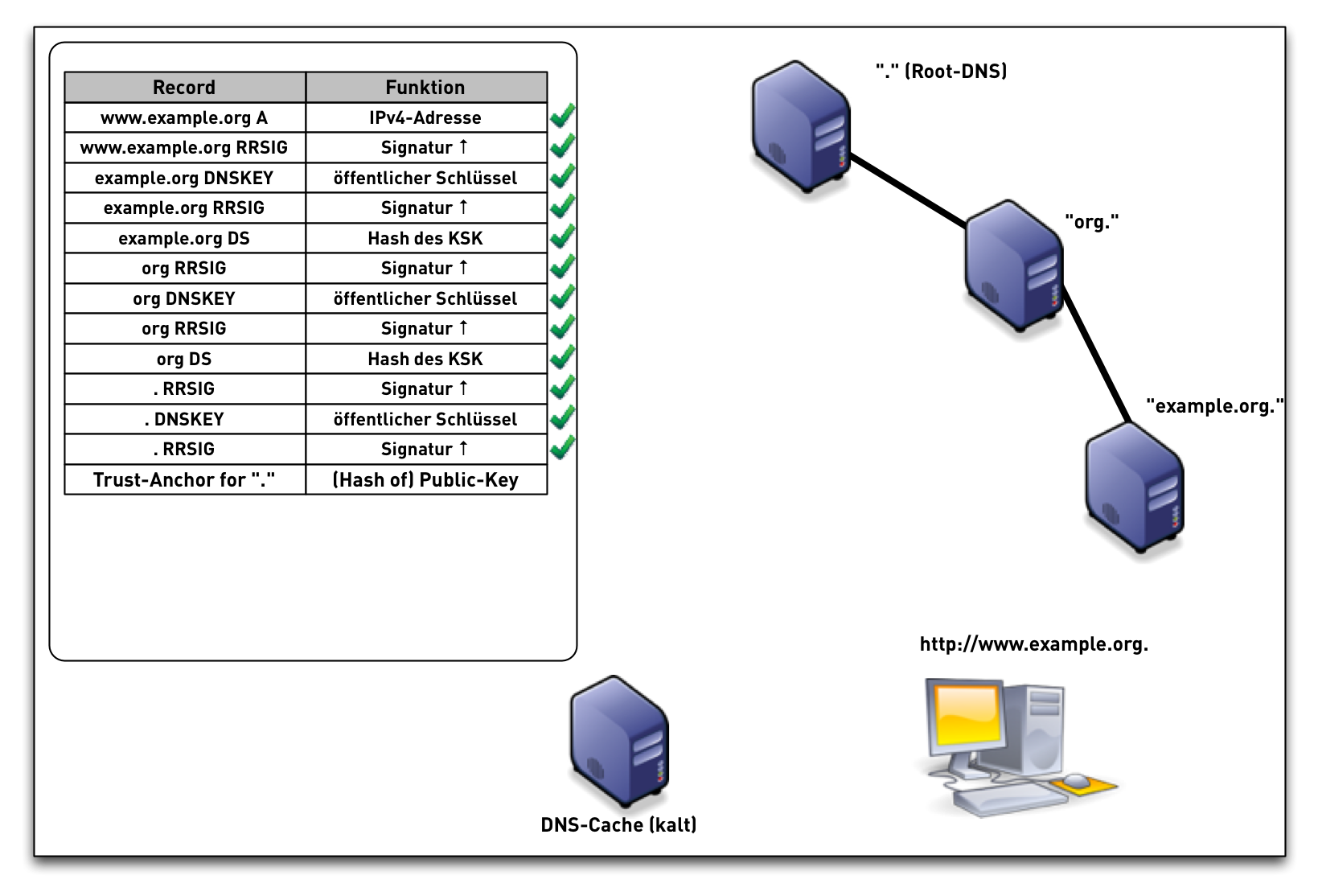

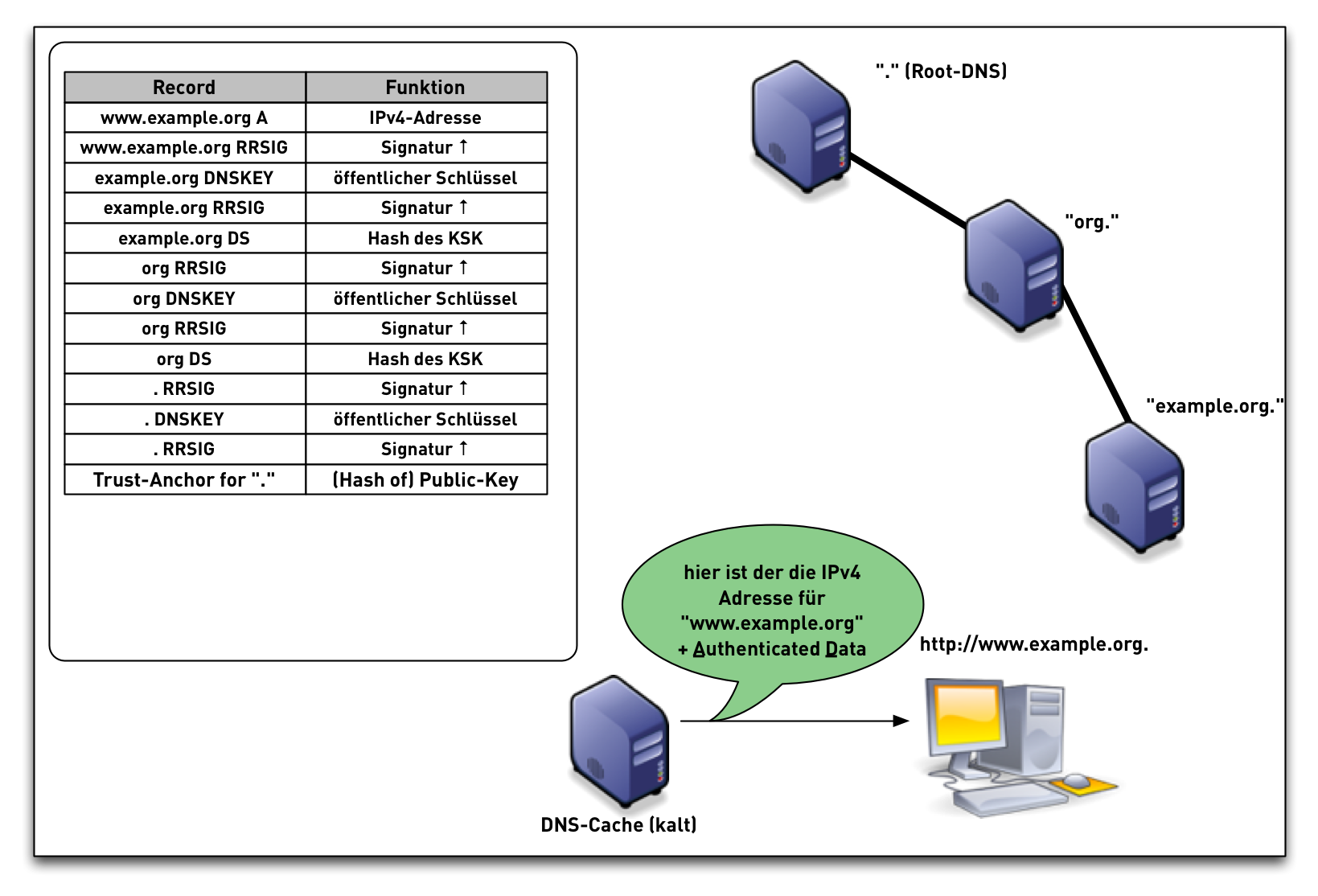

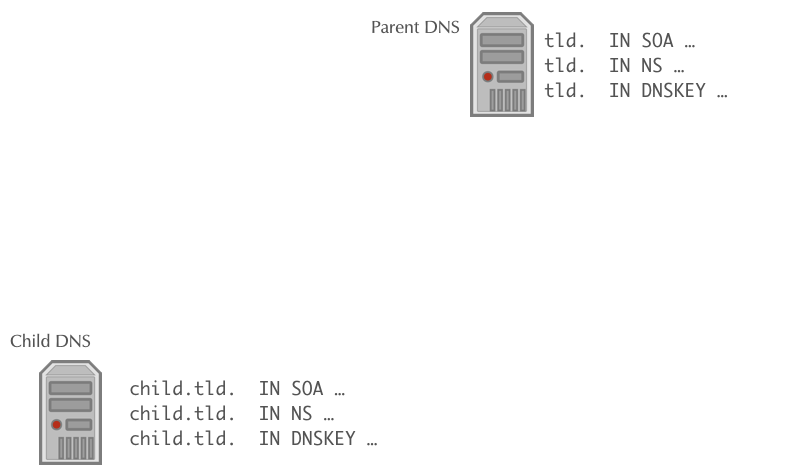

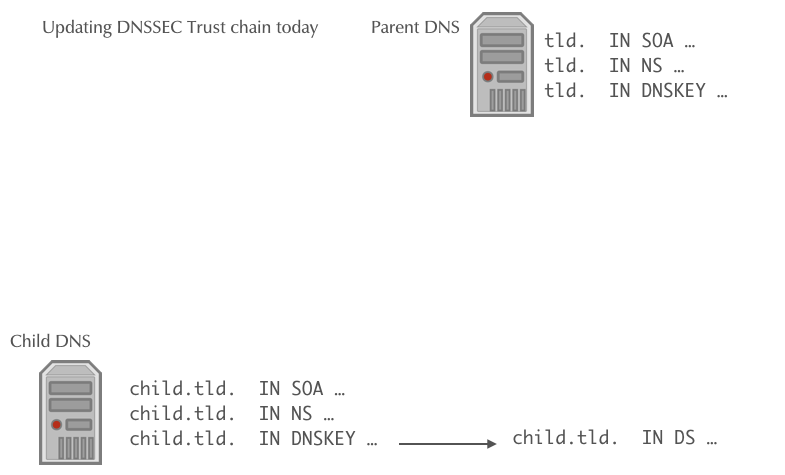

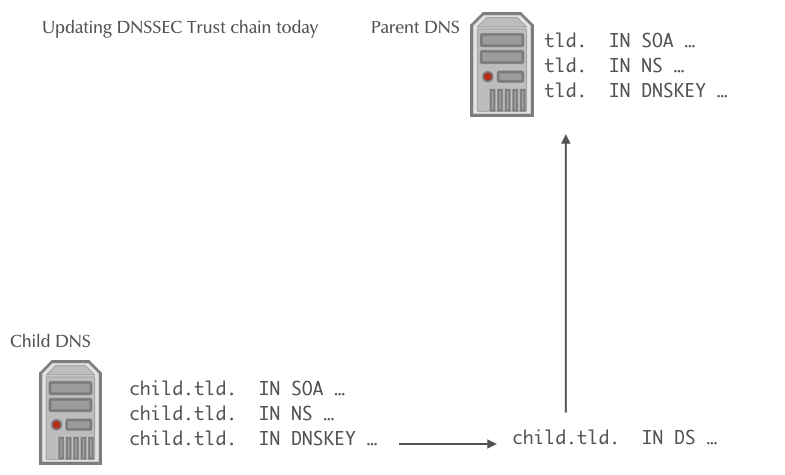

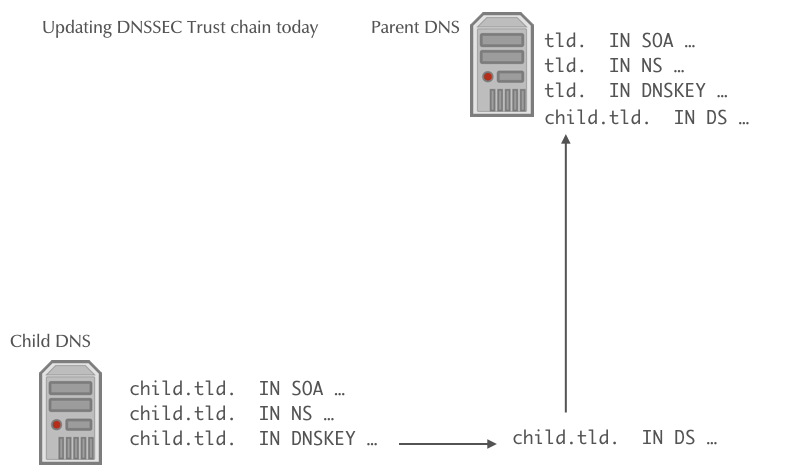

DNSSEC chain-of-trust

- DNSKEY records and Delegation Signer Records (DS-Records) build a chain-of-trust that proves that the DNS data is authentic

- The chain-of-trust is build up to a trust anchor (usually the KSK of the root zone, but can be further down the DNS delegation tree)

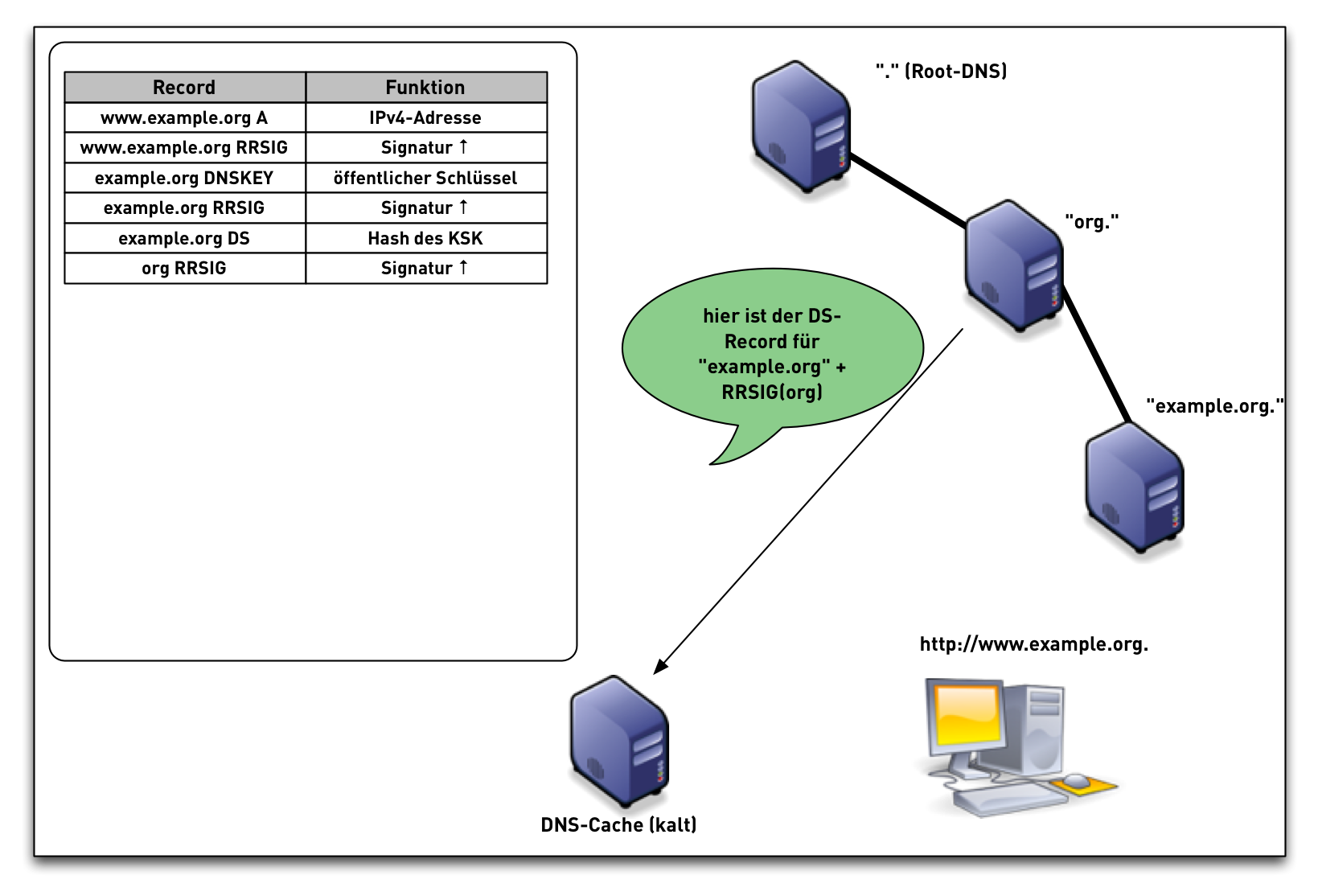

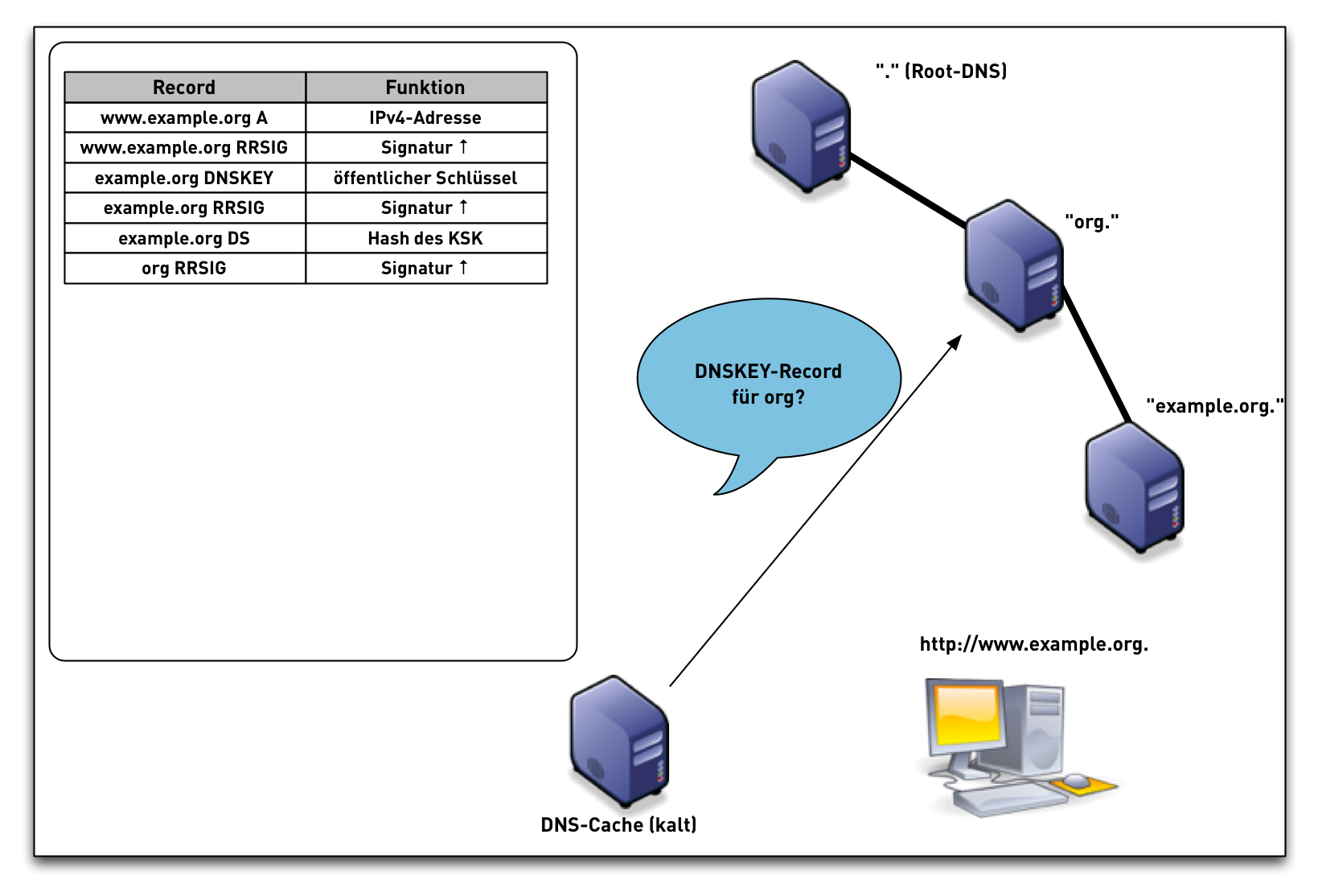

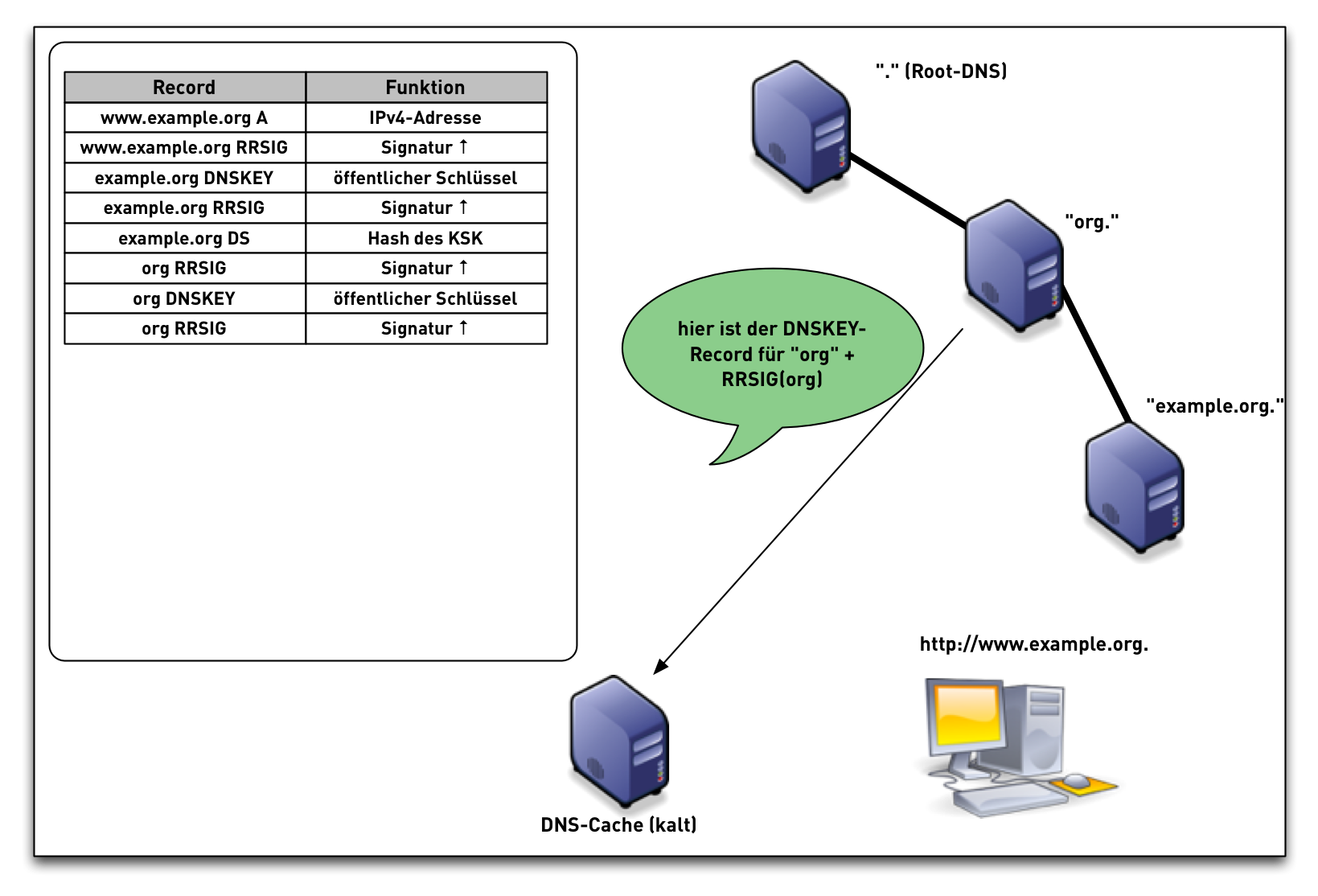

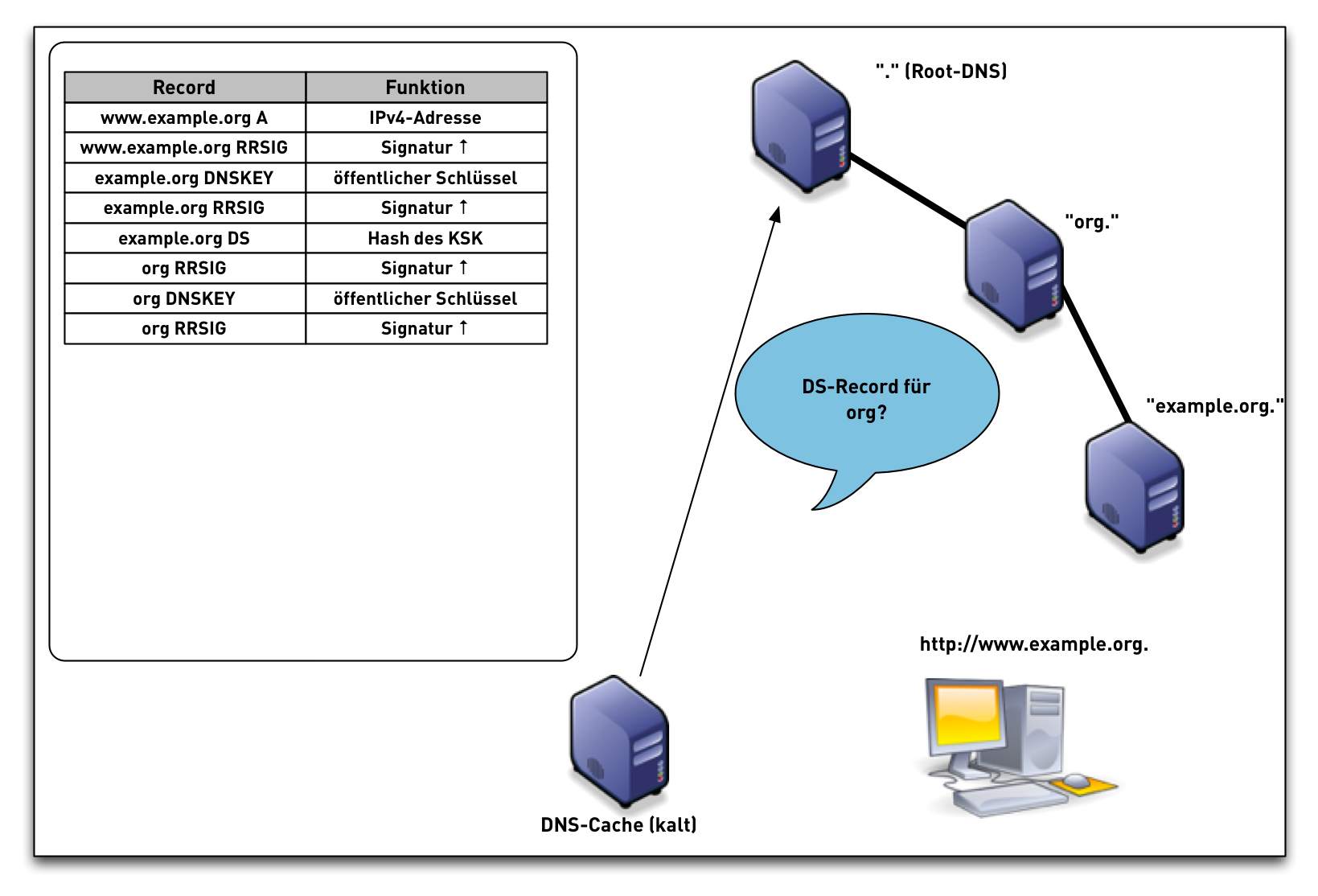

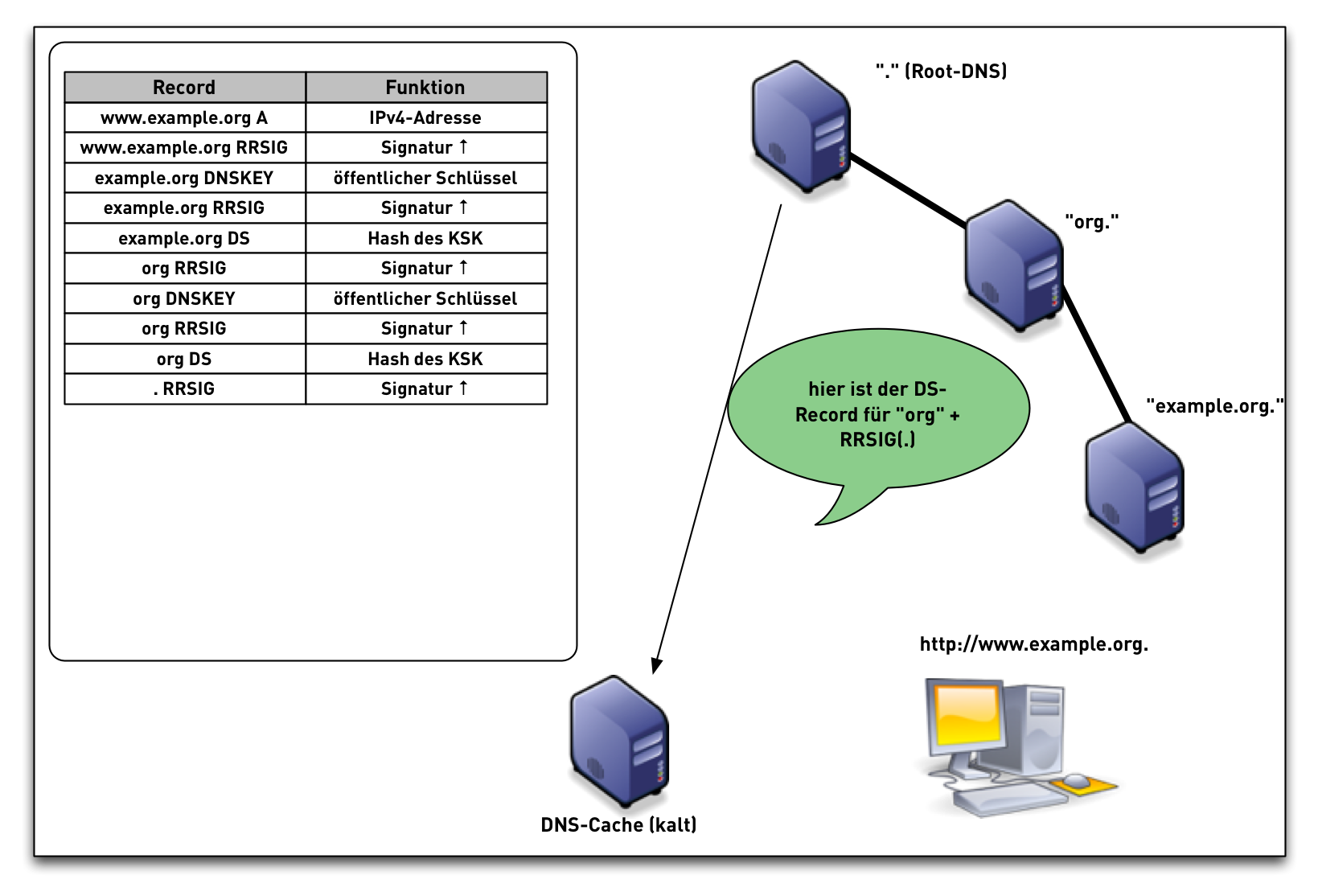

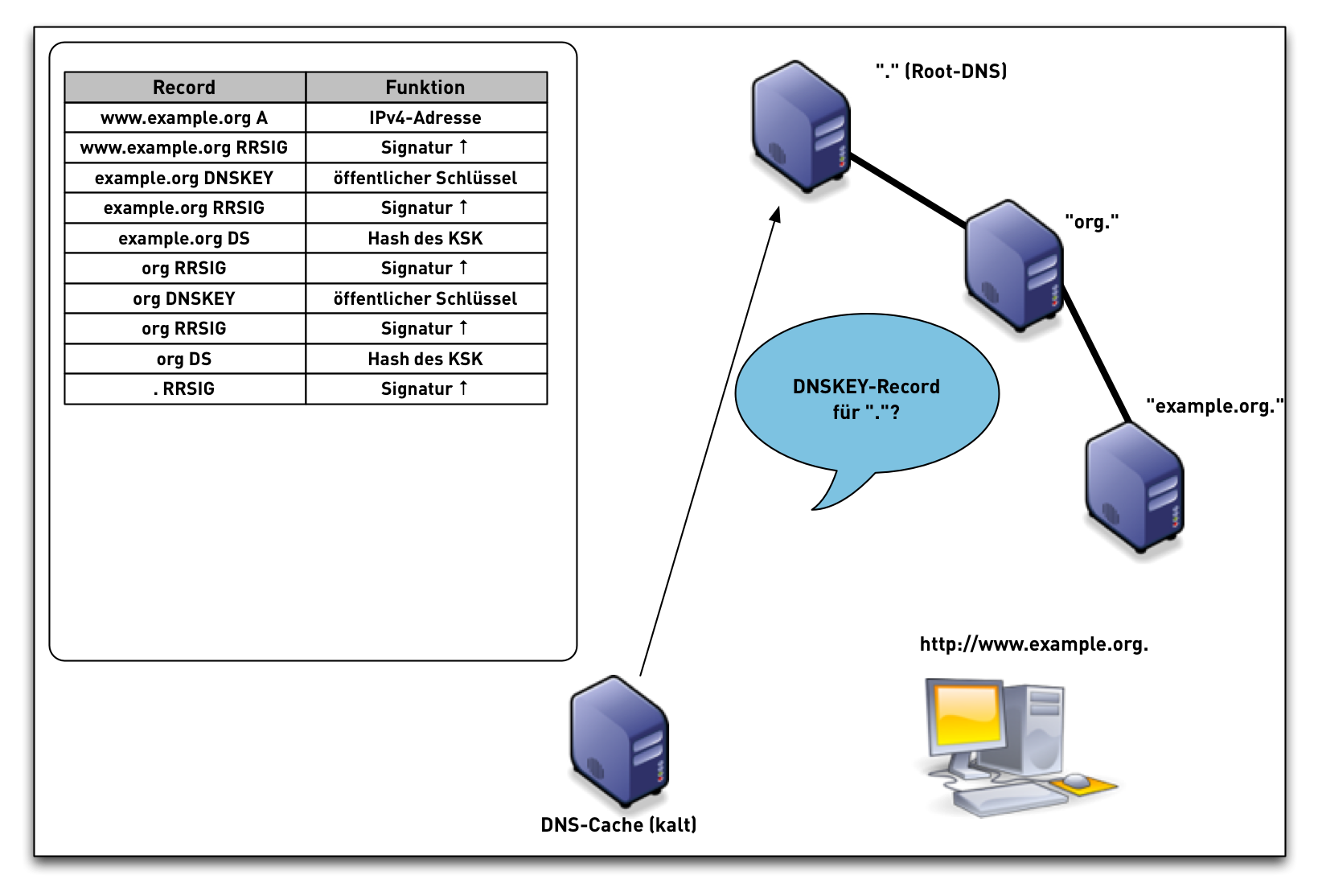

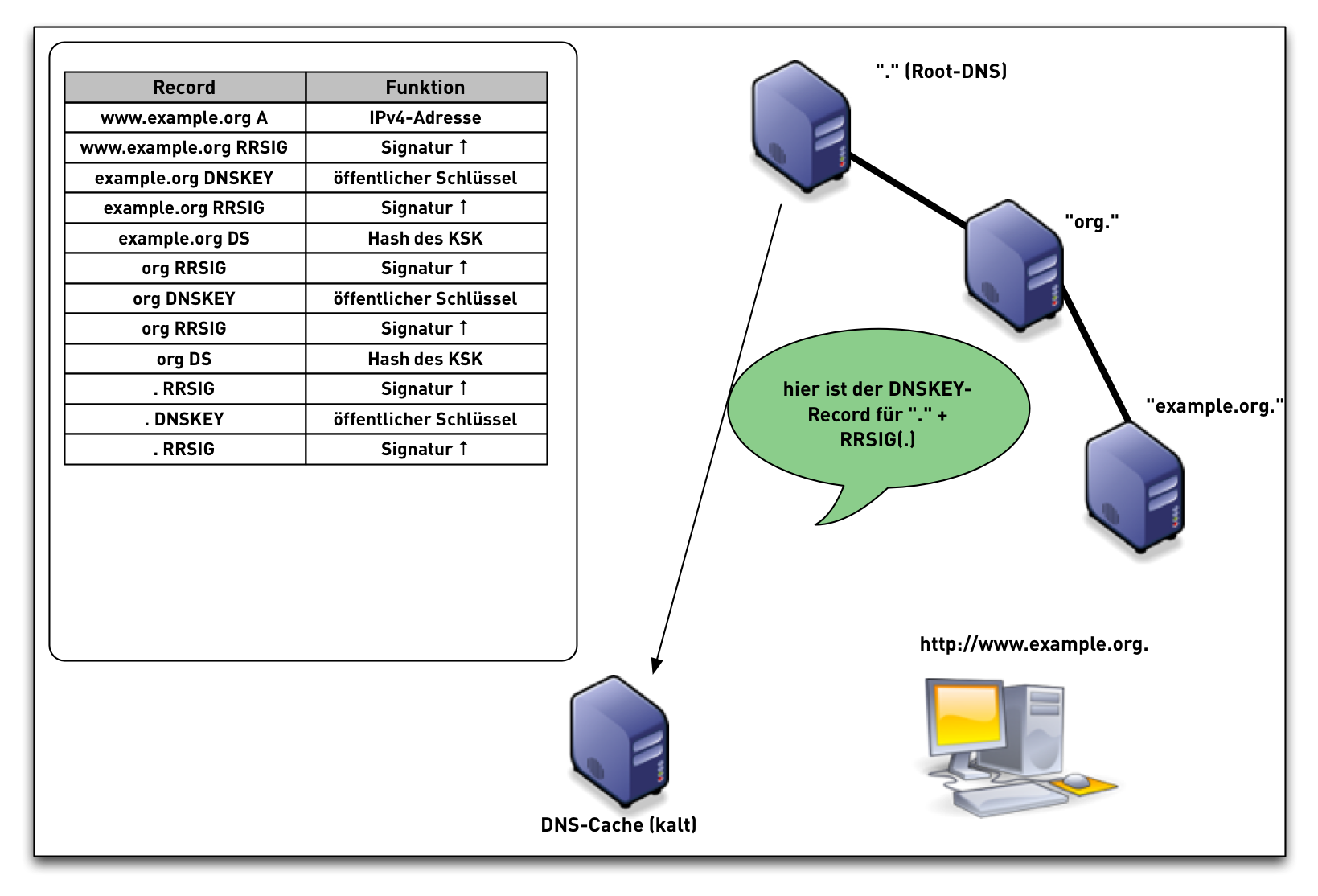

DNSSEC chain-of-trust

DNSSEC chain-of-trust

DNSSEC chain-of-trust

DNSSEC chain-of-trust

DNSSEC chain-of-trust

DNSSEC Keys

- In DNSSEC, each zone has one or more key pairs.

- The private key of each pair

- Is stored securely (probably on a hidden primary)

- Is used to sign zone data

- Should never be stored in a RR

- The public key of each pair

- Is stored in the zone data, as a DNSKEY record

- Is used to verify zone data

- The private key of each pair

DNSSEC Keys

- A private key signs the hashes of each RRSet in a zone.

- The public key is accessible through a standard RR.

- Recursive servers or clients query for the public key RR in order to verify a hash.

- The RR is known as the DNSKEY.

DNSSEC validation

DNSSEC validation (simplified)

- When the validator gets an RRSIG in a response, it needs the DNSKEY, and DS RR to authenticate.

- If validation fails, the signed RRs are discarded, and SERVFAIL error is returned to the client.

- If no appropriate trust anchor exists, the RRSIG is ignored.

- If the chain of trust is broken the signature is ignored.

- The steps in the following animation are simplified.

- It only shows validation using one key per zone (SSK/CSK).

- Commonly, a zone has ZSK & KSK, so there are additional steps.

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

DNSSEC Validation (simplified)

Strategies to Introduce DNSSEC

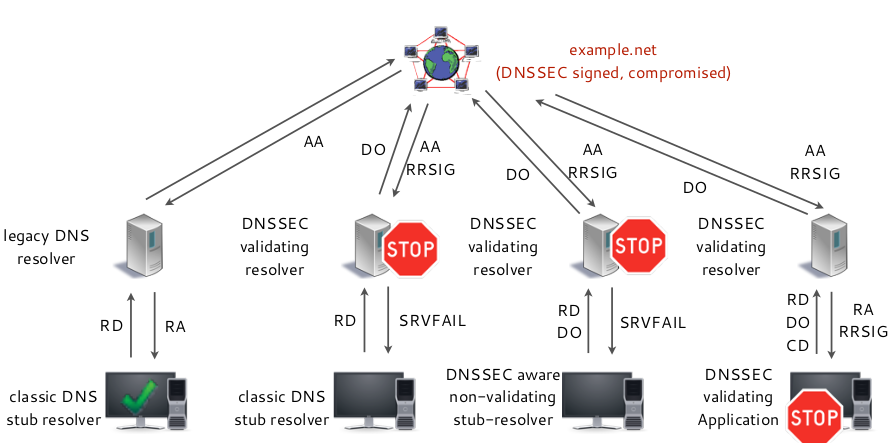

DNSSEC-Validiation at the Resolver

- There are many DNSSEC capable DNS resolver available

- BIND 9

- Unbound

- PowerDNS recursor

- Knot Resolver

- Windows Server DNS

- Nominum/Akamai

- …

DNSSEC-Validiation at the Resolver

- Most resolver today come with the trust anchor for the Internet

root zone preconfigured

- When using on the Internet DNS, these DNS resolvers do DNSSEC validation "out-of-the-box"

DNSSEC Resolver and time

- DNSSEC validation is time sensitive

- The DNSSEC signatures have expire and inception (become valid) times that the DNS resolver must check

- Without a correct time on the DNSSEC resolver machine, DNSSEC validation might fail

DNSSEC Resolver and time

- Recommendation: Implement automatic time synchronization for the DNSSEC resolver (NTP, PTP)

- Make sure the time synchronization has no dependency on (DNSSEC)

DNS name resolution (no circular dependecy or

chicken-and-egg-problem)

- A great usecase for Precision Time Protocol (PTP https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Precision_Time_Protocol) if available in the network

Trust anchor

- The DNSSEC Trust-Anchor (TA) in an DNSSEC resolver is an important security configuration

- The Trust Anchor is usually the Key-Signing-Key of the Internet DNS

root zone (or a hash thereof)

- Other trust anchors can be configured in addition

Keeping the trust in the anchor

- The trust anchor in DNSSEC can change over time (e.g. if the KSK of

the root zone changes as happen in October 2018)

- Management of trust anchor changes should be automatic (RFC 5011 Automated Updates of DNS Security (DNSSEC) Trust Anchors)

- Updates (automatic or manual) to the DNSSEC resolvers TA should be audited (monitoring)

- Access to the TA configuration should be limited

- A bad actor with access to a DNSSEC resolver can attack the users of that resolver

DNSSEC validation issues

- DNSSEC validation issues are rare

- Often DNSSEC validation issues are caused by operational issues

(expired DNSSEC signatures, DS record and DNSKEY KSK mismatch etc)

- A DNSSEC resolver cannot tell operational problems from attacks - but humans might

- Negative Trust Anchors can be used to disable DNSSEC validation for mis-configured domains

DNSSEC operational problems

- DNSSEC resolver monitoring is important to detect a high(er) rate of validation errors

- DNSSEC validation issues with less popular Internet destinations usually can be ignored (the owner will feel pressure to fix it)

- But sometimes, the domain owner is too big to fail…

DNSSEC operational problems

https://www.theverge.com/2021/9/30/22702876/slack-is-down-outage-morning-disruption-work-chat

Negative Trust Anchor

- Negative Trust Anchors are defined in RFC 7646 Definition and Use of DNSSEC Negative Trust Anchors

- Negative trust anchors (nta) disable DNSSEC validation for a

specific domain for a certain amount of time

- NTA can be used by operators in case a misconfiguration for a remote DNSSEC signed zone is detected. Care should be take to check that the DNSSEC validation failure is indeed a misconfiguration and not attack

- Domains with an NTA are processed as if there is no trust-anchor for that domain

Negative Trust Anchor in BIND 9

- NTAs are stored and are persistent across BIND 9 restarts

- BIND 9 checks the domain periodically. Once the domain starts validating again, the NTA for the domain is removed

- NTAs have a lifetime (maximum one week) and expire automatically

Example: adding an NTA (for 60 seconds):

% rndc nta -l 60 fail01.dnssec.works Negative trust anchor added: fail01.dnssec.works/_default, expires 18-Aug-2016 13:52:19.000 % rndc nta -dump fail01.dnssec.works: expired 18-Aug-2016 13:52:19.000 % ls -l /var/named/_default.nta -rw-r--r--. 1 root root 44 Aug 18 13:51 /var/named/_default.nta % cat /var/named/_default.nta fail01.dnssec.works. regular 20160818115219

Example: removing an NTA

% rndc nta -l 86400 fail02.dnssec.works # add a NTA for 1 day Negative trust anchor added: fail02.dnssec.works/_default, expires 19-Aug-2016 13:56:22.000 % rndc nta -dump fail02.dnssec.works: expiry 19-Aug-2016 13:56:22.000 % rndc nta -r fail02.dnssec.works # remove the NTA Negative trust anchor removed: fail02.dnssec.works/_default % rndc nta -dump # NTA is now gone

Recommendation for DNS resolver operators

- Make sure your DNSSEC validating resolver supports DNSSEC negative trust anchor

- Test the negative trust anchor function

- Document how to add a negative trust anchor

- If your software does not support automatic removal of NTAs, implement an automation (connected to your DNS resolver monitoring)

- Do not implement automatic NTA additions, activating an NTA should only occur after human inspection of the DNSSEC validation problem

Recommendation for DNS resolver operators

- Read the Internet Draft Recommendations for DNSSEC Resolvers Operators

Securing Zones with DNSSEC (signing)

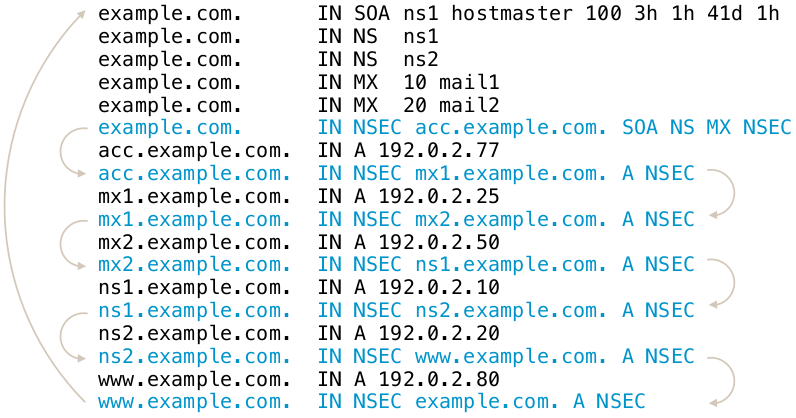

Authenticated Denial of existence - NSEC vs. NSEC3

- The RRSIG records in DNSSEC secure the positive answers from DNS (answers to queries where DNS records exist)

- But also negative answers need to be protected

- without protection for negative answers, attackers could spoof negative answers to launch denial-of-service attacks. The attacker can make DNS clients believe that a DNS resource does not exist

Authenticated Denial of existence

- DNS knows two kinds of negative answers: NXDOMAIN and NODATA/NXRRSET

- NXDOMAIN = the requested domain name does not exist

- NODATA/NXRRSET = the requested domain name does exist, but the requested record type does not exist for this name

- DNS error messages such as SERVFAIL, FORMERR or REFUSED cannot be secured with DNSSEC (these errors indicate errors in the protocol or in the DNS server infrastructure). If the protocol is broken, DNSSEC can't work either.

Authenticated Denial of existence

- The solution: the NSEC records in the DNSSEC signed zone create a

list of all existing data in the zone (domain names and records

types for the domain names)

- When returning a negative answer, the DNS server returns the negative answer containing the NSEC record (plus a signature for the NSEC record) which proves that the requested data does not exist in DNS

Authenticated Denial of existence

Issues with NSEC

- The NSEC record is an elegant solution to the problem, but it has

drawbacks:

- It is now possible for outsiders to list the complete zone contents by following the NSEC record chain. This is called zone walking

- For most zones this is not a big problem, as the DNS zone content is public anyway (SOA, NS records, WWW-A, MX records)

Issues with NSEC

- But it can be an issue for zones with sensitive content (email addresses, hostnames of critical infrastructure, new product names that should no go public yet)

- Operators of TLDs zones stay away from DNSSEC with NSEC, as it allows outsiders to record all changes to the TLD zone (new delegations and delegation removals)

- Example of zone walking:

$ ldns-walk isc.org

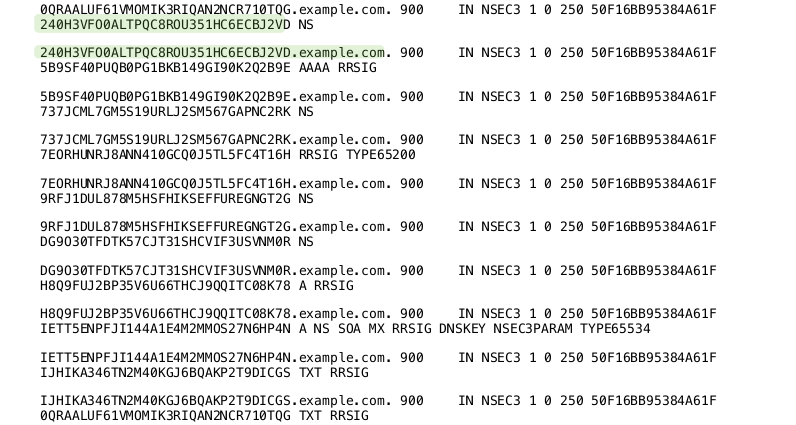

The NSEC3 record

- RFC 5155 (2008) defines the NSEC3 record as an alternative to NSEC

- All modern DNS servers support NSEC3

- The NSEC3 record works similarly to NSEC, with the difference that the link between the owner names is done using SHA1 hashes of the domain names instead of the clear text names

- NSEC3 makes it harder, but not impossible, to list the zone content

NSEC3 Chain

NSEC3-Parameter

- The NSEC3 record contains a number of parameters used for the

NSEC3 operation

- The hashing algorithm used (currently only SHA1 is defined)

- Flags: allows for DNSSEC opt-out in delegations.

- Number of hash iterations

- A salt value

NSEC3-Parameter Record

- Every zone with NSEC3 records contains an

NSEC3PARAMrecord. This record holds information needed by authoritative DNS servers to generate NSEC3 records for negative answers - Example: (SHA1, no flags, 20 iterations, salt value "ABBACAFE")

nsec3.dnslab.org. 0 IN NSEC3PARAM 1 0 20 ABBACAFE

NSEC3 iterations and salt

- The idea of the hash iterations in the NSEC3PARAM record was to

allow the operator of the zone to fine tune the work required for

calculating the hash

- A higher number of iterations should make it harder for attackers to brute force break an NSEC3 domain name

- A higher number also creates more CPU load for DNS resolvers that validate the NSEC3 records, making DNS name resolution slower

- The iteration parameter of an NSEC3 signed zone should be re-evaluated from time to time (yearly) to adjust the value for the technical progress

NSEC3 iterations and salt

- The salt should make it impossible for an attacker to pre-calculate rainbow tables for the zone

- The salt is a hexadecimal number, every hex digit contains 4 bit of information

Problems with NSEC3

- The iterations had more an negative impact on the CPU load of the authoritative DNS servers than preventing attacks

- The salt is not really needed, as each zone naturally has unique hashes so that a rainbow table for multiple zones is not possible

RFC 9276

- RFC 9276 - Guidance for NSEC3 Parameter Settings (Best current practice) gives updates guidelines for NSEC and NSEC3 deployments

- The iterations value should be set to

0(meaning 1 iteration of SHA1 hashing)- DNSSEC responses containing NSEC3 records with iteration counts greater than 150 are now treated as insecure by major DNS resolvers!

- As NSEC3 zones are inherently salted, the salt parameter should be

set to

- - The current recommendation for NSEC3PARAM is

1 0 0 -(SHA1 Hash, no flags, 1 iteration, no salt)

NSEC3 needed?

- Most DNS zone can work with NSEC instead of NSEC3

- Don't store names in DNS that should be secret (internal names, product names etc)

- DNS is a service to publish data, not for hiding data

ZSK and KSK split vs. CSK

- For organizational reasons, DNSSEC splits the chain of trust inside a DNS zone onto two different keys: the Key-Signing-Key (KSK) and the Zone-Signing-Key (ZSK)

KSK:

- The KSK generates only one signature: the signature over the DNSKEY record (RRset)

- The hash of the KSK is stored in the parent zone as the DS record. This hash is used to close the chain of trust from the parent zone to the DNSSEC signed zone. Each time the KSK in the DNSSEC signed zone is changed, the DS record in the parent zone must be replaced. The KSK has therefore a dependency on the parent zone.

- Because of this dependency with the parent zone, the KSK is usually a stable and strong key and not rolled often

ZSK:

- The Zone-Signing-Key does not have dependencies to external resources and can be rolled at any time

- Usually the ZSK is rolled often (and automatically), so the key does not need to be particularly strong

Single Signing Key

- DNSSEC does not require the KSK/ZSK split

- Depending on the security requirements, a DNS zone can be operated with just one DNSSEC key (single signing key)

- This key will be rolled occasionally (every few years)

- A single signing key requires a solid crypto algorithm for DNSSEC and good operational security for the private key

The need of key rollover

- The DNSSEC key material is public

- Including the signatures and the matching clear text (DNS record sets)

- The private key can get in un-authorized hands

- By accident

- By attacks on the signing server/HSM

- When using online-signing, the private keys must be live on the signing DNS server

- The key length or the algorithm used is not considered secure for a longer amount of time (for example 1024bit RSA keys)

The Challenges of DNSSEC key rollover

- The DNS is not consistent

- DNS zone data can differ for some time between authoritative server of the same zone (delay in zone transfer)

- DNS data is cached in DNS resolvers, operating systems, and applications

- During a DNSSEC key-rollover, the chain of trust must be un-broken at all times from all vantage points of the Internet

DNSSEC Keyrollover Documentation

- RFC 6781 - "DNSSEC Operational Practices, Version 2"

- RFC 7583 - "DNSSEC Key Rollover Timing Considerations"

Key rollovers, when and how often?

- DNSSEC keys do not have a technical lifetime, they don't expire

- The operational life time of DNSSEC keys is decided by the responsible administrator(s) and can be changed at any time

- The DNSSEC community has different views on KSK key rollovers

- Often and regularly

- Often but irregular (to not give attackers information when the system might be more vulnerable due to the key rollover)

- Only if there is evidence that the key has been compromised or stolen

Key Rollover automation

- Most authoritative DNS server offer key rollover automation

- BIND 9

- Knot

- PowerDNS

- Microsoft Windows DNS

- OpenDNSSEC to automate DNSSEC management for DNS server software that does not bring its own automation

- The one step that often still needs manual work is the update of the DS record in the parent zone …

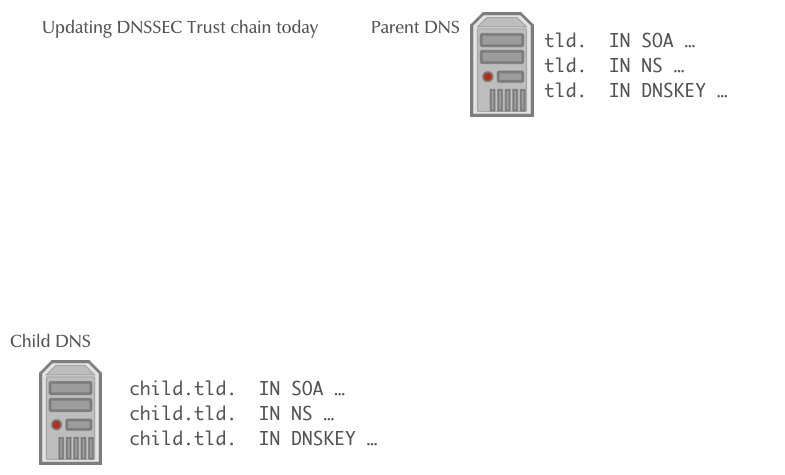

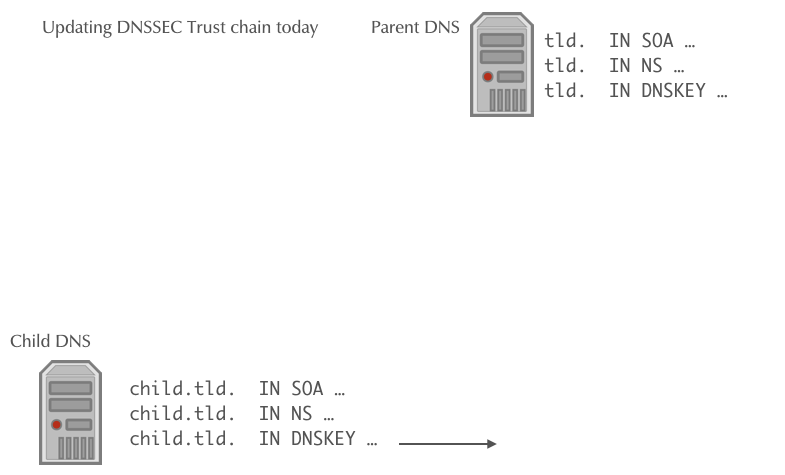

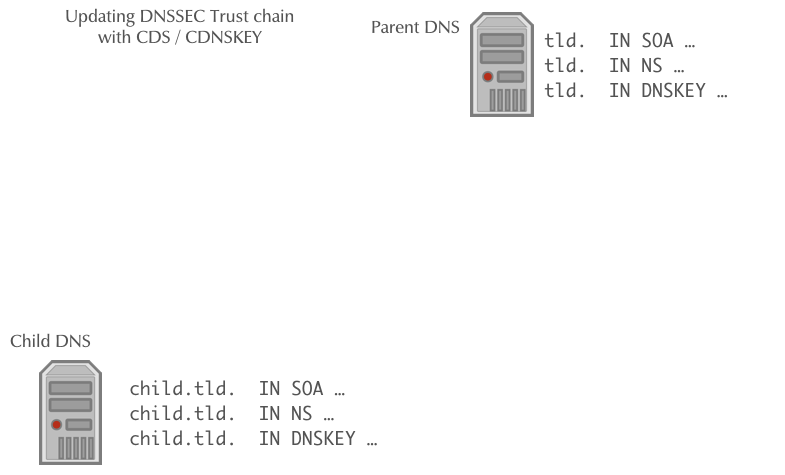

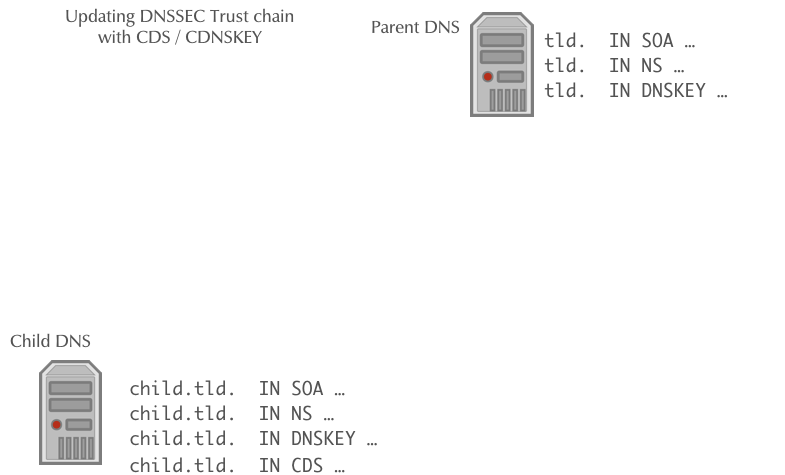

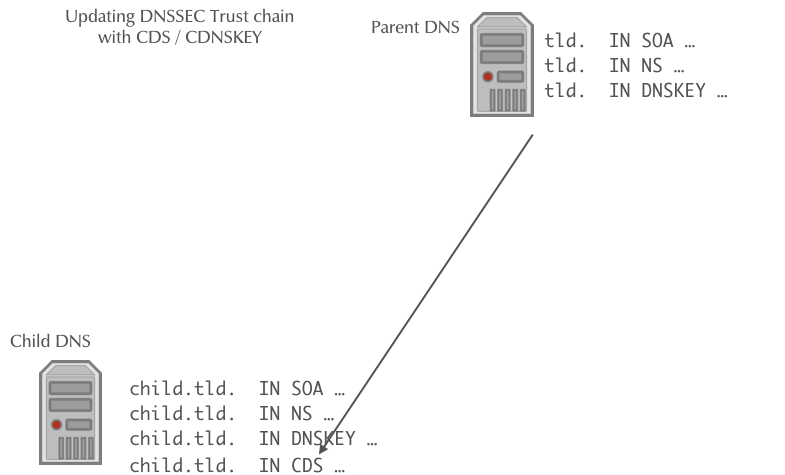

Automating DNSSEC Delegation Trust Maintenance (RFC 7344/8078)

- RFC 7344/8087 defines an automatic way to update the chain of trust towards the parent zone in an KSK key rollover

- The operator of the zone creates a new KSK for the zone and then publishes the new DS record or/and DNSKEY record for the parent zone in a CDS and/or CDNSKEY record in the zone

- The authoritative DNS server for the parent zone periodically polls the child zones for new CDS or CDNSKEY records

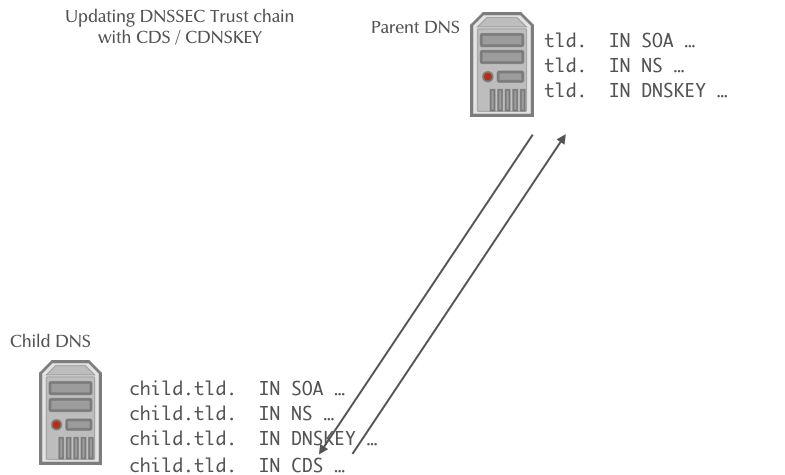

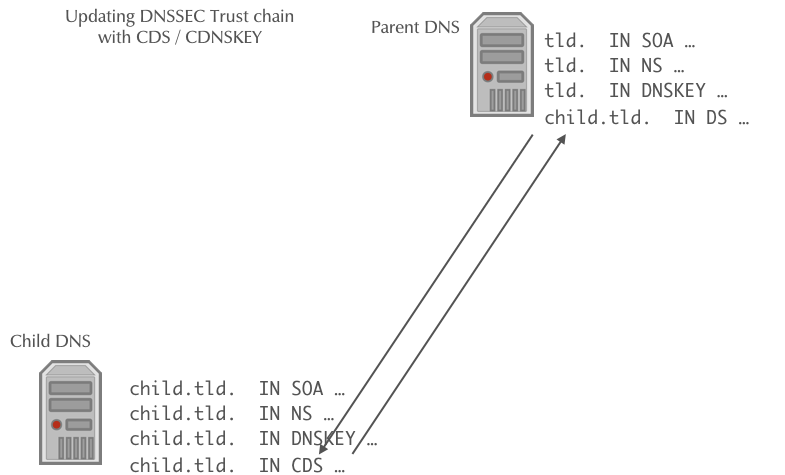

DNSSEC Rollover automation

- Once a new CDS record is found, it will be validated against the

current KSK and DS records, and if it is valid, it will be imported

into the parent zone (replacing the DS record)

- If a new CDNSKEY record is found in the child zone, the authoritative DNS server of the parent zone will validate the record, calculate the hash to get a DS record, and will then replace the DS record with the newly calculated DS record

- BIND 9 supports CDS and CDNSKEY since version 9.11

- The

dnssec-cdsutility can change DS records for a child zone based on CDS/CDNSKEY records - CDS and CDNSKEY is already supported by some TLDs (czech republic ".cz". Switzerland ".ch", Lichtenstein ".li" …)

CDNSKEY/CDNS

CDNSKEY/CDNS

CDNSKEY/CDNS

CDNSKEY/CDNS

CDNSKEY/CDNS

CDNSKEY/CDNS

CDNSKEY/CDNS

CDNSKEY/CDNS

CDNSKEY/CDNS

CDNSKEY/CDNS

CDNSKEY/CDNS

Reducing Risks of DNSSEC Operations

Risk: operating a DNSSEC validating resolver

- A DNSSEC validating resolver will respond with the DNS error

SERVFAILto the DNS client whenever it detects a mismatch in the DNSSEC chain of trust or a bogus or expired DNSSEC signatureSERVFAILis not DNSSEC specific, there are many error

situations that can result in an SERVFAIL response

- the end user cannot detect that the DNS name resolution fails

because of DNSSEC security and will blame the operator of the DNS resolver for the outage

Risk: operating a DNSSEC validating resolver

Solutions to mitigate this issue

- Open communication with the end user about DNSSEC issues

- Active monitoring for DNSSEC validation issues on the DNS resolver

- Prepare for the use of Negative Trust Anchor (NTA)

- Enable Extended DNS Error Messages (EDE RFC 8914 Extended DNS Errors) if available

Risk: DNSSEC signed zone with NSEC3

- An authoritative DNS server with an NSEC3 DNSSEC signed zone must

calculate one or more SHA1 hash(es) for every negative DNS

response (NXDOMAIN or NODATA)

- This yields the risk of Denial-of-Service attacks against the

authoritative server due to CPU resource exhaustion

Solutions: DNSSEC signed zones with NSEC3

- Consider employing NSEC instead of NSEC3. "zone walking" might be no or the smaller issue

- Provision enough CPU resources for the maximum amount or queries

that can reach the DNS server (network capacity)

- Test the server capacity

- Enable response rate limiting on the authoritative DNS server(s)

Risk: DNSSEC signed zone

- Errors during the signing process

- Error while publishing/replacing the DS record in the parent zone

- Error while refreshing the DNSSEC signatures (RRSIG records)

- Errors during key rollover

- Operational issues because of too large DNS response packets (>1232 byte)

- DNSSEC validation issues because of messy DNS resolution path (CNAME redirections between DNSSEC signed and unsigned zones)

- DNS errors because of Parent/Child zone disagreement (NS records in parent zone delegation do not match NS records in the zone)

Solutions: DNSSEC signed zones

- Errors during the signing process:

- Learn and test on toy domains, get practice

- Get external know how for the introduction of DNSSEC in your zones

- Get DNSSEC training for the DNS administrators

- Adjust the TTL values of the zone (should be below 24 hours, better below 2 hours)

- Adjust the SOA values of the zone

(Refresh/Retry/Expire/NegTTL). Too large values can be problematic.

Solutions: DNSSEC signed zones

- Errors while publishing/replacing the DS record in the parent zone

- Test the new DS record locally (for example with

unbound-host) before submitting to the operator of the parent zone - Test with a locally created root DNS server

- Monitor the status of the DS record and the KSK in the zone

- Automate the update of the DS record with an API

- Test the new DS record locally (for example with

Solutions: DNSSEC signed zones

- Errors while refreshing the DNSSEC signatures (RRSIG records)

- Automate the refresh of signatures (BIND 9, PowerDNS, KnotDNS, Windows 2012/2016, OpenDNSSEC …)

- Monitor the expiry of signatures in the zone

Solutions: DNSSEC signed zones

- Errors during key rollover

- Become familiar with DNSSEC key rollovers; practice them

- Get external help, DNSSEC training

- Automate key rollovers

- Monitor key rollovers

- Create a written key rollover journal (helps when working as a team)

Solutions: DNSSEC signed zones

- Operational issues because of too large DNS response packets

(>1232 byte)

- Adjust the EDNS0 buffer size on all authoritative DNS servers of the DNSSEC zone to 1232 byte

- Carefully select the domain names to make use of label compression

- Prevent large DNS resource record sets

- Stay away from large RSA DNSSEC keys and signatures, use EC algorithms

- Prevent CNAME chains

- Enable minimal-responses

- Enable minimal-any

Solutions: DNSSEC signed zones

- DNSSEC validation issues because of messy DNS resolution path

(CNAME redirections between DNSSEC signed and unsigned zones)

- Balance the name resolution path between redundancy and DNS resolution steps (always a good idea)

- Prevent CNAME redirection from DNSSEC signed zones to in-secure DNS zones

Solutions: DNSSEC signed zones

- DNS errors because of Parent-Child-Zone Disagreement (NS records

in parent zone delegation do not match NS records in the zone)

- Make sure the delegation NS records in the parent zone match the NS records in the zone

- Monitor for parent-child NS record mismatch

Risk: DNSSEC

- Is DNSSEC a risk for the network?

- Yes, but it is a risk that can be mitigated with planning, automation, and careful work

- The DNSSEC benefits outweighs the risks

Selecting a DNSSEC algorithms

| Algorithm | No. | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | deprecated, not implemented | |

| 5 | not recommend, deprectated for DNSSEC signing, not supported in Red Hat Enterprise Linux 9 (and up) | |

| RSASHA256 | 8 | recommended |

| RSASHA512 | 10 | large keys, large signatures, risk of UDP fragmentation or TCP fallback |

| 3 | deprecated, slow validation, no extra security | |

| 12 | deprecated | |

| ECDSA | 13/14 | small signatures, read RSA vs ECDSA for DNSSEC |

| ED448/ED25519 | 16/15 | not supported by legacy resolver RFC 8080 / RFC 8032 Edwards-Curve Digital Signature Algorithm (EdDSA) / Assessing DNSSEC with EdDSA |

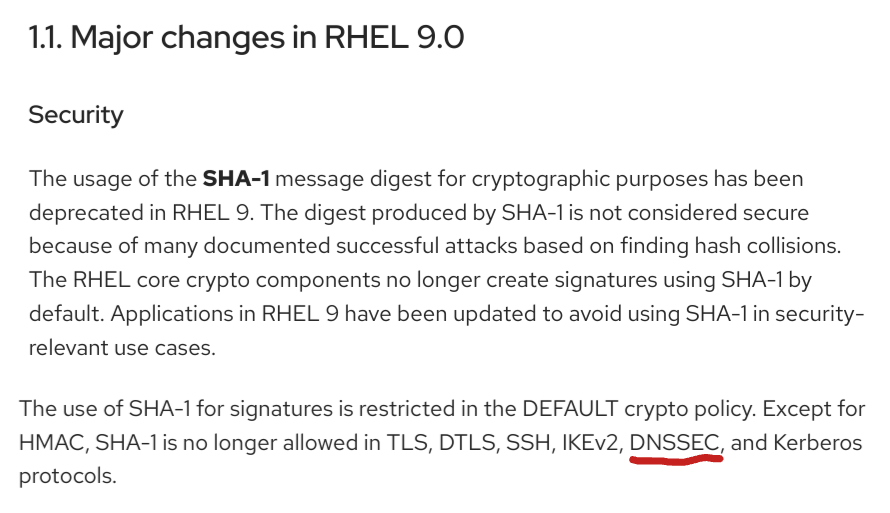

SHA1 phase out in Red Hat EL 9

https://access.redhat.com/documentation/en-us/red_hat_enterprise_linux/9/html/9.0_release_notes/overview

Avoid SHA1

- The hash algorithm SHA1 is weak

- It should be phased out for existing DNSSEC zones

- It should not be used for new DNSSEC deployments (use RSASHA256 or ECDSA)

- Double-Signing zones with SHA1 and other (stronger) algorithms does not help as downgrade attacks are possible

Avoid UDP fragmentation

- UDP fragmentation can be used to attack DNS traffic

- There is a specific danger for DNS resolver that does not validate

DNSSEC

- But receive DNSSEC signed data, as DNSSEC signatures create large(r) DNS responses

- BSI Study: IP Fragmentation and Measures against DNS Cache Poisoning (Frag-DNS)

Avoid UDP fragmentation - DNS authoritative Server operators

- Avoid old(er) Linux kernels that are vulnerable to MTU downgrade attacks through ICMP spoofing (Long-Term/Enterprise Kernel)

- Configure the authoritative DNS server with an maximum UDP answer size of 1232byte (EDNS0 Buffer Size)

- Make sure the authoritative DNS server does respond on TCP port 53 (See RFC 7766 - DNS Transport over TCP - Implementation Requirements)

- DNSSEC sign your zones so that resolvers can validate

Avoid UDP fragmentation - DNS Resolver operators

- Enable DNSSEC validation

- Configure the authoritative DNS server with an maximum UDP answer size of 1232byte (EDNS0 Buffer Size)

- Make sure the DNS resolver can query DNS content over TCP

- Block fragmented DNS responses coming from the Internet in the Firewall (they should never occur with an EDNS0 buffer of 1232byte)

Thank you!

Questions?